By Libby Motika

Palisades News Contributor

Photos courtesy Pine Ridge Girls’ School

A few days before Christmas in 2015, Santana Janis, a 12-year-old Lakota Indian, decided that she did not want to live anymore.

The incident sparked a series of New York Times articles that revealed a shocking spate of suicides among Lakota youth, mostly girls between the ages of 12 and 24.

Pine Ridge Reservation, home of the Oglala Sioux tribe, drew national attention that year after nine young people killed themselves during a four-month period, and another 103 attempted suicide during the same period.

Statistics deliver cold facts and alert us to a disturbing malaise that expresses the despair and hopelessness experienced by some Native American youth, Robert McSwain, acting director of the Indian Health Service, told Congress in 2015.

Behind the data are precious children, sacred to the Lakota, who live with the legacy of oppression, lack of economic opportunity, and high levels of drug and alcohol use around them.

For Victoria Shorr, reading about the Pine Ridge suicides exploded in her mind and sparked a startling insight at a time when she was already reassessing her own goals in life.

“I was taking a walk by myself in Temescal Canyon and I was thinking I’ll never get my book published and then I saw a California king snake. It jolted me. Even though I thought I would never start a girls’ school again, when I got to thinking about Pine Ridge, I couldn’t just forget about it.

The Pacific Palisades resident, who had cofounded the Archer School for Girls in 1995, began to envision a college-prep school for girls on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota.

Shorr certainly had her challenges in founding Archer back when the trend in private education was for girls’ schools to join forces with boys’ schools. It was her single-minded belief in the benefit of single-sex education for girls that propelled her optimism. But Shorr soon realized that duplicating the Archer model would not work at Pine Ridge.

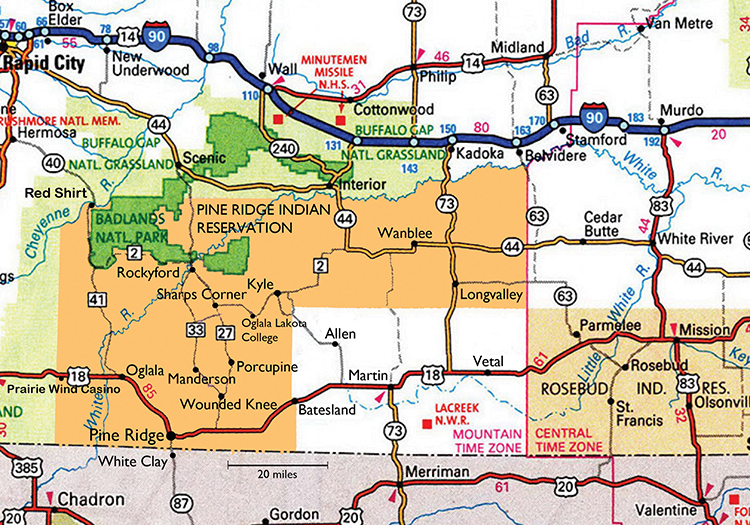

The Pine Ridge Reservation is a vast windswept land of stunning grasslands and dusty plateaus the size of Delaware and Rhode Island combined.

Officially, there are 20,000 reservation inhabitants, but officials believe there are twice that many. The tribe has suffered centuries of injustices, including the confiscation of the Black Hills by the U.S. military in 1876, which broke up the Great Sioux Reservation, and then in 1890, the Wounded Knee Massacre that resulted in the death of some 300 Lakota at the hands of the U.S Army.

The reservation is the third-poorest place in America, with an average income of $3,500. There is no grocery store on the reservation; the nearest is 90 minutes away in Rapid City.

The state of education at Pine Ridge is severely lacking in multiple areas. The school dropout rate is over 70 percent, and the teacher turnover rate is eight times that of the national average.

“What we needed wasn’t just any old girls’ school,” Shorr explains. “Before we teach these girls geometry we have to deal with the trauma that every single girl has undergone, either experienced or witnessed.

“We had to empower these girls before we could educate them, which turns Archer’s mantra on its head: Education through empowerment instead of empowerment through education.”

Says Lakota native Cindy Giago, head of Pine Ridge Girls’ School: “The problem with reservation schools is that I don’t think we challenge the students enough. There is a stigma around Native Americans related to drugs and alcohol. We are lowering our expectations of them.”

Before the school opened its doors in August 2016, much preparation had taken place. “Our strategy began with planning with the community,” Giago told the News. “What did you want to see in a school? The elders advised us not to teach about the culture, but rather to let the culture teach us. Lakota first!” The founders hired a skeletal staff and started with seven sixth- and seventh-graders. They advertised in the local newspaper for interested students.

“The application essays were intended mostly for the purpose of getting to know the girls,” Giago says. “The personal interviews with the girls and their families gave us an idea of what our students are dealing with.”

The curriculum is 50/50 Common Core standards and Lakota history and culture. Lakota cultural lifeways are woven in all ways into the life at the school.

“There is a coming-of-age ceremony, when each girl is given a Lakota Spirit name,” Shorr says.“We respect and eat the buffalo and offer the hide for people to sit on when they’re upset. We do a ‘wiping of the tear’ ceremony when somebody loses a family member.”

The history curriculum includes world history and U.S. history, taught through a Lakota lens. James Loewen’s “Lies My Teachers Taught Me,” the American Book Award-winner and national bestseller that revitalizes the truth of America’s history, explores how myths continue to be perpetrated. The textbook dispels the idea that American history pits evil white people against saintly natives. Rather, Loewen insists that the history show that natives and whites influenced each other’s cultures in profound ways.

To make history relevant to the students locally, the teacher talks about the tribe’s lost land, what happened at Pine Ridge, or the heroism of the men who fought in World War II.

“After the Standing Rock [pipeline] stand-off last year, the girls went up there and they wrote a letter to the governor of North Dakota explaining why the science of the pipeline was faulty,” Shorr says. “That inspired me to ask the Di Caprio Foundation for a grant to pioneer a curriculum called the science and politics of water that we can share through Indian Country. We got the grant and we’re doing it.” The school now enrolls 15 girls, four in 6th grade and 11 in 7th.

Their week begins Monday morning with a purification circle, an adila, where the girls burn sage to eliminate any negative energy that may have upset them over the weekend.

At 10 a.m., they enter the Inipi, or sweat lodge. Within the enclosure, constructed of willow branches covered with canvas, they build a fire, which when burned to embers is doused with water. Much like a sauna, the sweat-lodge experience grounds the girls for the school tasks ahead.

While these ceremonies are valuable and meaningful, the girls also need someone from the outside they can talk to, says Giago. A counselor comes to the school every week to talk to the girls, understanding that this is a very delicate age.

The school also offers art, music—and sports, in which they compete well, despite the fact they lack a gym. They placed fifth in the Big Foot Conference in volleyball and basketball, Giago says. Their team name is Kahtella, warrior women.

President Shorr presides over a 14-member board, comprising eight white members and six natives. While on campus, she meets with the girls but doesn’t impose. She is careful to respect their ideas and recalls a mis- take early on.

“They wear uniforms for all the reasons they wear uniforms at Archer and Marlborough,” Shorr explains. “We got them polo shirts and skirts. But they like to wear leggings or long skirts, as do the older Lakota women. They showed their resistance by demonstrating that they did not want to look like white girls.

“My idea was that they’d look like Archer girls, but they said ‘No.’ That’s okay, I don’t impose.”

Funded by private donations and foundations, Pine Ridge Girls’ School has ambitious plans that include establishing greenhouses and gardens, health and wellness screening, and ongoing counseling to the students and their families, while building an eventual endowment.

“Our wish is that the girls are proud and secure wherever they are,” Giago says. “A lot of times we hear ‘I have to be a different person to fit into the broader culture.’ My granddaughter, who is a Stanford senior, told me ‘I do not walk in both worlds. I am Lakota wherever I go.’”

For more information, contact pineridgegirlsschool.com.

You must be logged in to post a comment.