By Libby Motika

Palisades News Contributor

Photos courtesy J. Paul Getty Museum

As the exuberance of the Getty Center’s visually stunning PST/LALA “Golden Kingdoms” subsides, museumgoers are invited to another small but colorful treat, an example of the institution’s curatorial excellence.

In studying the Getty’s extraordinary collection of 18th-century pastels, Associate Curator of Drawings Emily Beeny and Drawings Conservator Michelle Sullivan made a fascinating discovery, which is revealed in “Pastels in Pieces,” now on view through the end of July.

In the 18th century, paper was made by hand, rolled in sheets no wider than a person’s outstretched arms. Until the beginning of that century, pastel artists worked on a small scale, but soon began to compete with oil painters for major commissions by piecing together multiple sheets of paper to create large, continuous surfaces for their work.

In the Getty exhibition, a sharp-eyed visitor can spot where the paper has been pieced together by the artist, who does his best to conceal the join, either by embedding it in folds of luxurious clothing, hiding it in shadow, or distracting the eye by shifting the center of focus away from the seam.

Piecing may also conceal a mistake. If the artist doesn’t like a particular portion of the work, he cannot paint over it, as he could with oil. He will redo the section involved and simply paste it over the offending part.

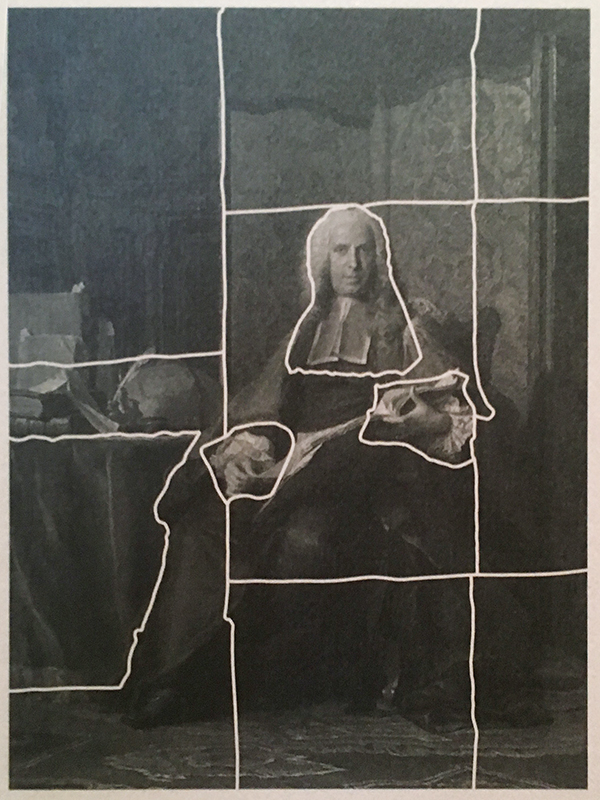

The monumental portrait of Gabriel Bernard de Rieux is one of the largest pastels made in the 18th century by Maurice Quentin de La Tour, who was renowned for endowing his sitters with a distinctive air of charm and intelligence and capturing the delicate play of facial features.

It’s pieced together with 12 separate sheets of paper in a more or less continuous support that could rival the monumental scale of an oil portrait. La Tour also used piecing, working up the sitter’s head and each of his hands on a separate sheet.

“La Tour could work out the details of the face on a separate piece of paper and essentially paste it on a body, probably posed by a model,” Beeny says. “Bernard de Rieux was a powerful, wealthy man who would not have had the time to sit around for a long period of time for a portrait.”

We credit Venetian portraitist Rosalba Carriera for sparking the widespread interest in pastel portraits in Paris in 1720-21 with her visit to influential collector and connoisseur Pierre Crozat, who was eager to tap a new prosperous buying public.

Carriera also expanded the usefulness of the medium by developing a method of mixing the colored chalk with a binder and shaping it into sticks, which led to a much wider range of prepared colors.

The works in the Getty exhibition provide a perfect lesson in the advantages of pastel over oil.

Certainly, one of the most practical considerations of the medium is the speed in which a pastel can be finished, requiring fewer sittings. “Rosalba was reported to do a portrait in under three hours,” Beeny says.

“The artist didn’t have to wait for oil layers to dry. Pastels also had a great advantage in their velvety tones, which is made possible by the uneven reflective surface of the chalk rather than the smoother surface of oil paint. Each of these little tiny particles throws off light in every direction.”

Indeed, pastel was praised for the lifelike quality, or “bloom,” it conferred upon its subjects.

The “Self-Portrait” by Charles-Antoine Coypel offers some information on the technical process.

“I love the pleasant fiction of an artist at work wearing an elaborate powdered wig, lace sleeves and velvet coat,” Beeny says. “This is not a working outfit, yet it does give us a glimpse into his process and how the pastels were made. Peeking out of the portfolio are sheets of blue paper on which this pastel has been set against. Also, you see the crayon carrier, which allows the artist to work without dragging his sleeve across the paper.”

Blue paper, which was the chief alternative to white paper, was made from the rags of workmen’s clothes. Besides being cheap, it also was prized for its rugged texture that allowed the artist to work the dry pigment into the fibers of the paper.

Unlike oils, which can be mixed on a palette from nine or 10 basic pigments, each tone in pastel required a different stick, with artists making use of hundreds of crayons.

“In many of these works, there is actually a lot of wet work happening, an artist going back with a brush or sometimes even mixing the pastel with water and going back over,” Beeny says. “Those areas read as a matte, and the dry areas tend to be a bit more powdery or luminous.”

There were a lot of secrecies around the pastel techniques, especially surrounding the use of fixatives that could be applied to keep the dusty layer in place. Proprietary recipes for fixatives were closely held; de La Tour had his own recipe for fixative, which ironically critics thought ruined his work. It was recognized that applying a resin to the surface of a pastel would darken the colors and cause them to yellow.

Because pastels are susceptible to the threats from vibration and light, they are stored flat under their protective glass, in the dark, at the Getty—until now, when they have made their way to the wall in this gem of an exhibition.

By combining this kind of scholarly research and collaboration as between curator Beeny and conservator Sullivan, the Getty can advance the possibility of these small, exquisite exhibitions.

You must be logged in to post a comment.