By Laurel Busby

Staff Writer

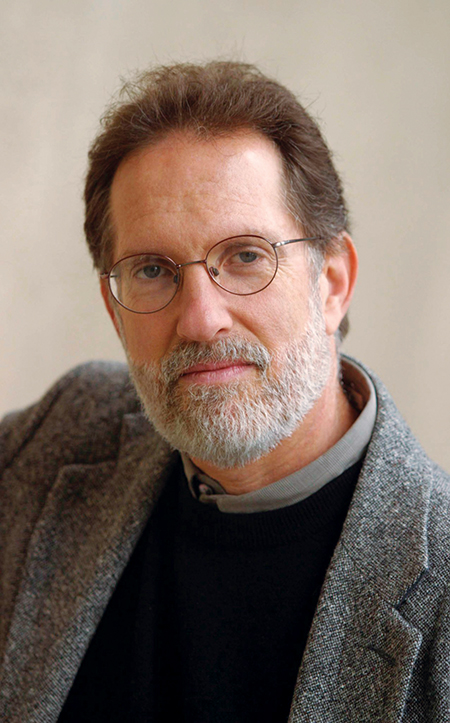

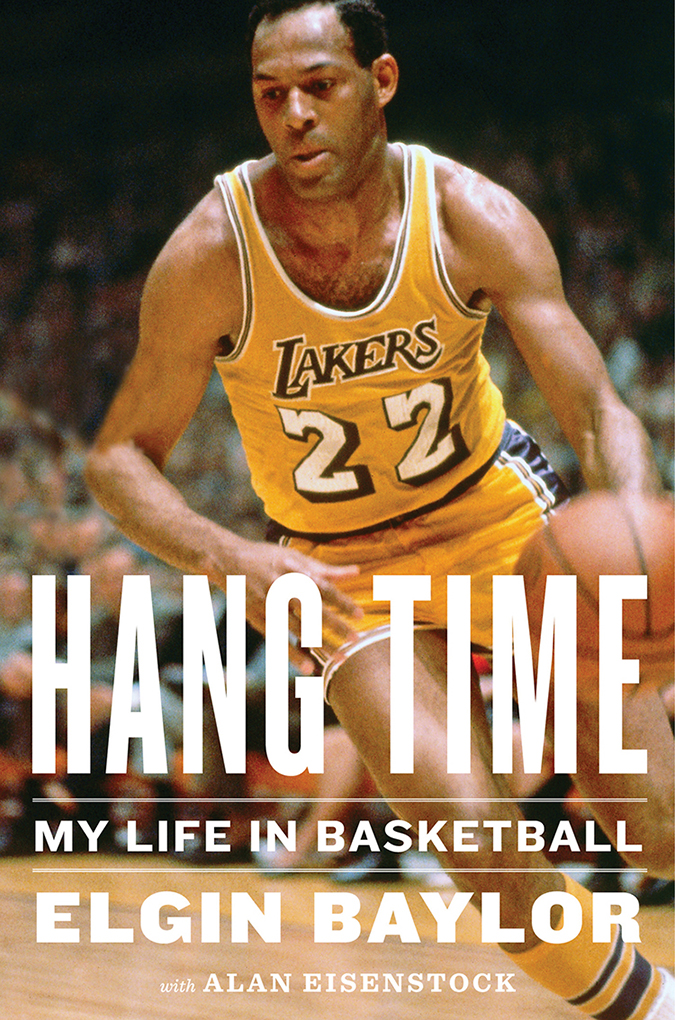

On Friday, Elgin Baylor, a game-changing superstar from the early L.A. Lakers, was honored with a statue outside Staples Center, and his memoir, written with Palisadian Alan Eisenstock, is being released.

The book, “Hang Time,” was a delight to write for Eisenstock, who spent many months visiting each afternoon with Baylor, now 83, and his wife, Elaine, at their Beverly Hills home. Eisenstock often brought a bottle of wine, and they sipped and reminisced about both Baylor’s glories and his traumas playing basketball and growing up in a segregated Washington, D.C.

“It was an absolute labor of love doing this book,” said Eisenstock, a longtime basketball fan who has written multiple memoirs. “It was really joyful. I think they looked forward to my coming over there. I really did look forward to going over there. It didn’t feel like work.”

The trio got along well from their first meeting. “I loved him, and I loved Elaine,” Eisenstock said. “He’s such a gentle soul. I just felt something deep about him.”

The book they created together, which by chance coincided with the statue planning and installation, opens with an airplane trip the trio took two years ago. Strangely enough, Jerry West, Baylor’s close friend and former teammate who also has a statue at Staples Center, happened to be sitting across the aisle from Baylor.

West told his friend that he was pushing for a statue to commemorate him, and Baylor, who played for 14 seasons as a Laker and led the team to multiple trips to the NBA championship finals, imagined how nice a statue would be. Baylor will be the ninth person and the fifth Laker to receive this honor. The statue inscription, which Eisenstock wrote, lists some of Baylor’s achievements, including selection as the NBA’s No. 1 draft pick in 1958, Rookie of the Year honors, 11-time NBA All Star, 27.4 points per game average, and his election to the NBA Hall of Fame in 1977.

In addition, it reads, “Elgin Baylor—the first Los Angeles Lakers superstar—was a once-in-a-lifetime player. A true innovator, influencer, dynamic scorer, and dominant rebounder. Often copied but never equaled, Elgin literally changed the sport itself from a game played methodically, on the ground, to one played spontaneously, acrobatically, above the rim. On the court and off, he rose above all obstacles in his path, including racism. He faced life the same way he played the game—powerfully, with dignity and class. Elgin Baylor was an inspiration to his contemporaries and to everyone who has ever since played the game.”

The inscription also would aptly describe the book, which details Baylor’s early life and development, his personal challenges, and his many failed attempts to bring the Lakers an NBA championship.

From the beginning, his mother was a constant support to him, while his father was a challenging, often angry man whom he only began to understand as an adult. Racism was rampant, and the police repeatedly took his brothers to the station even though they had committed no crimes. Officers even came into their home and forced his father to beat Baylor’s sister in one of the book’s most powerful and illuminating moments.

This incident “was such a difficult thing for him to experience,” Eisenstock said. “It was very painful.”

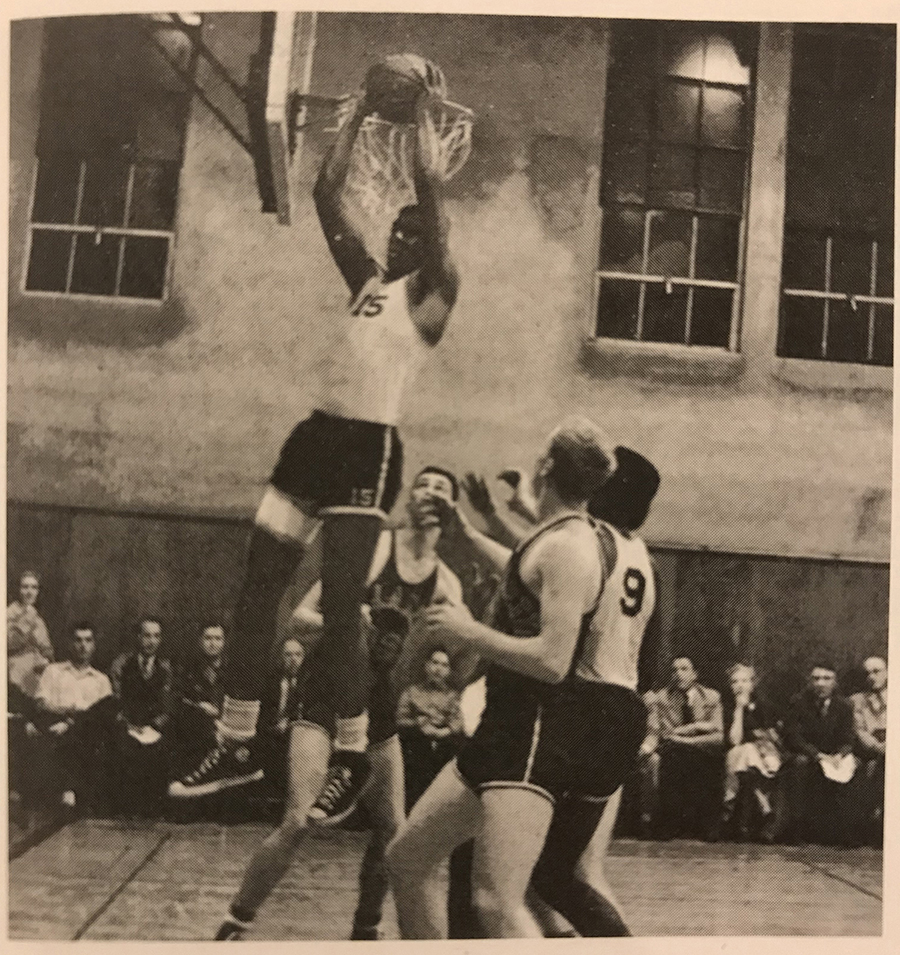

Most of Baylor’s childhood was spent in D.C., where he learned to play basketball secretly at night in the amenity-filled whites-only park. Across the street was the blacks-only park, which was one step up from a field. Eventually, the black park got a hoop, and it became his after-school haunt.

“Basketball was his escape, and I don’t know if you want to call it therapy, but it was in a way,” Eisenstock said. “He was always most comfortable playing basketball.”

Baylor practiced feints to get other players to commit before he did. He learned to time his jumps, so that he was going up while his defenders were coming down. But he also brought a spontaneity to the game that Eisenstock likens to jazz music.

“I don’t think he did the same thing twice. He just kind of invented the game. He made the game spontaneous—when you look at old footage, players, not only are they not capable of stopping him, they also stopped what they’re doing and they look at him. They gawk at him and say, ‘What the heck?’ It’s wild.”

Baylor’s entrée into the NBA was not an easy one. First, the major local paper, the Washington Post, only covered games at white high schools, and the black high schools were not allowed to play against them. So there was little media attention to alert colleges to his skills.

Despite this, in 1954, Baylor earned a scholarship to the College of Idaho, and also began his first foray into integrated society. He later transferred to Seattle University, and eventually declared his intention to be drafted before graduating.

At the time, the NBA was relatively slow about integrating its teams. The first three black players were drafted in 1950, and when Baylor joined the Minneapolis Lakers in 1958, he was one of only three black players on the team. Some cities were still segregated and unwelcoming.

For example, a hotel once declined to provide rooms to the three blacks, so Baylor chose not to play in that game. His actions meant he received hate mail and threats, but it also changed the league as the NBA created a policy forbidding hotels from discriminating against players.

“There’s a thread of racism that runs through his life,” said Eisenstock, who also touches briefly on the documented racism of Donald Sterling, whom Baylor later worked for as the L.A. Clippers’ general manager. “It kind of just continued. Elgin, he wasn’t an activist, but he took strong stands in a very dignified way . . . [Before writing the book], I knew about his physical strength as a player, but I wasn’t aware how strong he was as a person.”

Eisenstock and Baylor will sign copies ofHang Time at Diesel Books on April 26 at 6:30 p.m. Eisenstock will also speak at the Palisades Library on May 17 at 6:30 p.m.

You must be logged in to post a comment.