By Libby Motika

Palisades News Contributor

For Ray Juncosa, who was open to sharing a cabin on his month-long photographic expedition to Antarctica, the ideal roommate would be someone with a passionate interest, who had the wherewithal to afford such a trip, and could “elbow aside” a whole month. A not-so-subtle description for Ray himself, who has the stamina for such a challenging adventure, a “good eye,” and most important, the temperament for the patient, quiet observation necessary to capture the landscape and wildlife, in particular the penguins and their extraordinary behavior.

No stranger to adventurous, off-the-beaten path excursions, the Pacific Palisades resident has documented his travels throughout most of the continents, with one special trip a 10-week journey from Istanbul through Central Asia to Beijing by Land Rover.

After a 42-year career in institutional and construction management for the public sector, Juncosa has found an exhilarating new freedom to focus on the many adventures that await.

The photographic journey to Antarctica began as a kind of answer to the “call of the wild.”

He was perusing a pamphlet put out by Joseph Van Os, whose photo safaris have been the world leader in innovative photography tours and workshops since 1980. He signed on.

The scope of the trip was the wide swath of sea and ice in the South Atlantic, including stops at South Georgia Island, the Falklands and Antarctica.

In November 2013, Juncosa and 70 other passengers boarded the ship in Ushuaia, the capital of Tierra del Fuego, commonly regarded as the southernmost city in the world.

The early stops were brief, a day and a half in Tierra del Fuego, then two to three days on the Falkland Islands, visiting penguin and albatross colonies. They continued steaming for another few days to reach South Georgia, where the group spent a week going in and out of various bays and harbors.

The “Ushuaia” often moored offshore and dispatched small inflatable boats, Zodiacs, to navigate the inlets.

Noting that Van Os tours are meticulously well planned, Juncosa understood that the inlets and bays for landings might very well be inaccessible, as the ship could be blocked by dense pack ice or because some beaches were engulfed by windblown ice that rubber Zodiacs could not penetrate. But there were always alternative plans providing for good photography subjects.

“South Georgia is way out in the middle of nowhere, one-third of the way from the tip of South America to the tip of Africa,” Juncosa says. “It’s 130 miles long, so if you think about Catalina, it would the distance from Huntington Beach to Santa Barbara.”

Juncosa was beguiled by what he called the geologic feel, with mountains 10,000 ft. above sea level. “It felt like going to the Himalayas.”

The adventurers then proceeded to Antarctica, both the east side and the west side, before returning to Ushuaia by crossing the infamous Drake’s Passage, so named for its propensity for high winds and rough seas, referred to as the “Drake Shake.” Juncosa was not able to report on his passage, given that he slept through it all.

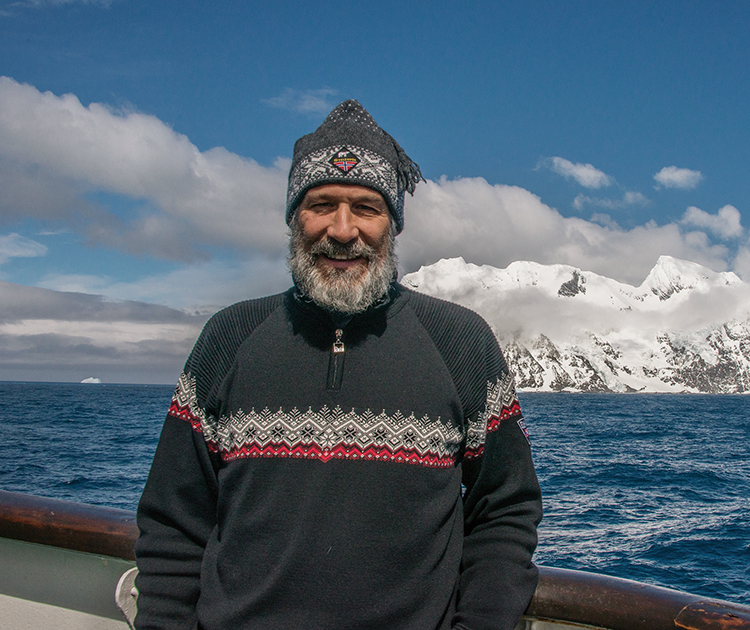

Tall and fit with a neat, adventurer’s gray beard, Juncosa likes to embark on excursions with no preconceptions, and not too much research. While on board, the ship’s professional specialists offered talks and films on aspects of the journey.

“I hadn’t studied penguins,” he says. “I take pictures; I like the way they come out. Let’s call it an artistic expression, without having to train my hands like a Dali or Michelangelo.”

Equipped with a “ton” of camera equipment, Juncosa took thousands of photos, often closely recording the behavior of pelagic birds, which he began to compare to some very human patterns. They are a pacific bird, perhaps due to the fact they have few predators. They seem to tolerate both other species and curious large birds like the albatross or the vulture-like caracara that inhabit the Falkland Islands and Tierra del Fuego.

He doesn’t use a tripod, preferring to adjust the speed of the film. “The tripod is useful for nighttime shots, but if you’re on a boat, what are you going to do with a tripod?” Of the 11 different penguin species, Juncosa saw seven. While the emperor penguin is most familiar to us, thanks

to the 2005 movie The March of the Penguins, they live in the interior of Antarctica, where Juncosa’s voyage did not penetrate.

Perhaps the closest species to the emperors are the king penguins, whose plumage is similar but who have a broad bright orange cheek patch contrasting with surrounding dark feathers and yellow-orange color at the top of the chest.

The kings lay only one egg at a time, which they carry around on their feet covered with a flap of abdominal skin. Similar to the emperors, incubating duties are shared between dad and mom, allowing the off-duty parent to go off to sea on an extended food foraging trip.

Antarctica.

Photos on this page: Ray Juncosa

Despite the king penguins being popular with tourists, mainly on the Falklands and South Georgia, so far the impact of tourism is very low. In fact, Juncosa was able to approach his subject (as long as he didn’t enter a colony) with no reaction. He did find that the click of the camera shutter caused the curious bird to turn and look at him.

The rockhopper penguins are the smallest species, distinct from others by the black spiky feathers on their head. Rockhoppers usually find their habitat in rocky shorelines, where they make nests and burrows in tall grasses. Because of the harsh rocky environment, they cannot slide on their bellies like most penguins, so they hop to get from one place to another.

Like so many advanced photographers, Juncosa was smitten as a young boy. He was an adventuresome child, spending afternoons in the Palisades romping in the outdoors.

His parents moved to El Medio in 1955, and apart from 14 years in the Bay Area, Ray has always lived here. He and his wife Liz have a son, Mark, who is vice president of vehicle engineering at SpaceX.

Ray obtained his first camera, a $2 Brownie, at age 12 by redeeming Lipton teabags.

“I remember a trip we took to Mesa Verde,” he says, amused by his innocence. “I was lining up a picture of cliff dwellings, when all of a sudden I bumped into something: ‘Kodak Spot.’”

He uses Nikon almost exclusively, “because my father gave me a vintage 1960 Nikon. But as the American photographer and conservationist Art Wolfe says, ‘They never ask what camera you use.’ They ask ‘what picture you got. It’s the photographer who matters.’”

So impressed with the Van Os organization, Juncosa joined an expedition to Patagonia soon after, photographing the vast windswept semi-arid plateau that encompasses over one-third of Argentina and Chile.

You must be logged in to post a comment.