Most of us have heard of the Silk Road, certainly Marco Polo, but the details may be fuzzy, swathed in a centuries-old opaque history involving myriad rulers, merchants and religious seekers.

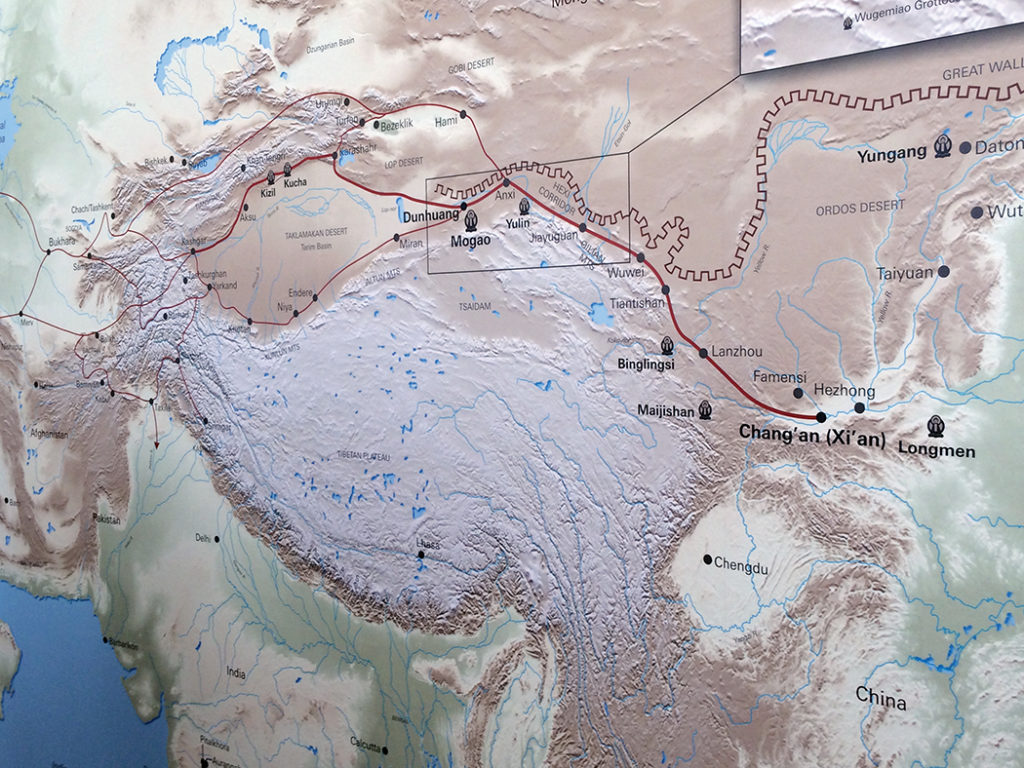

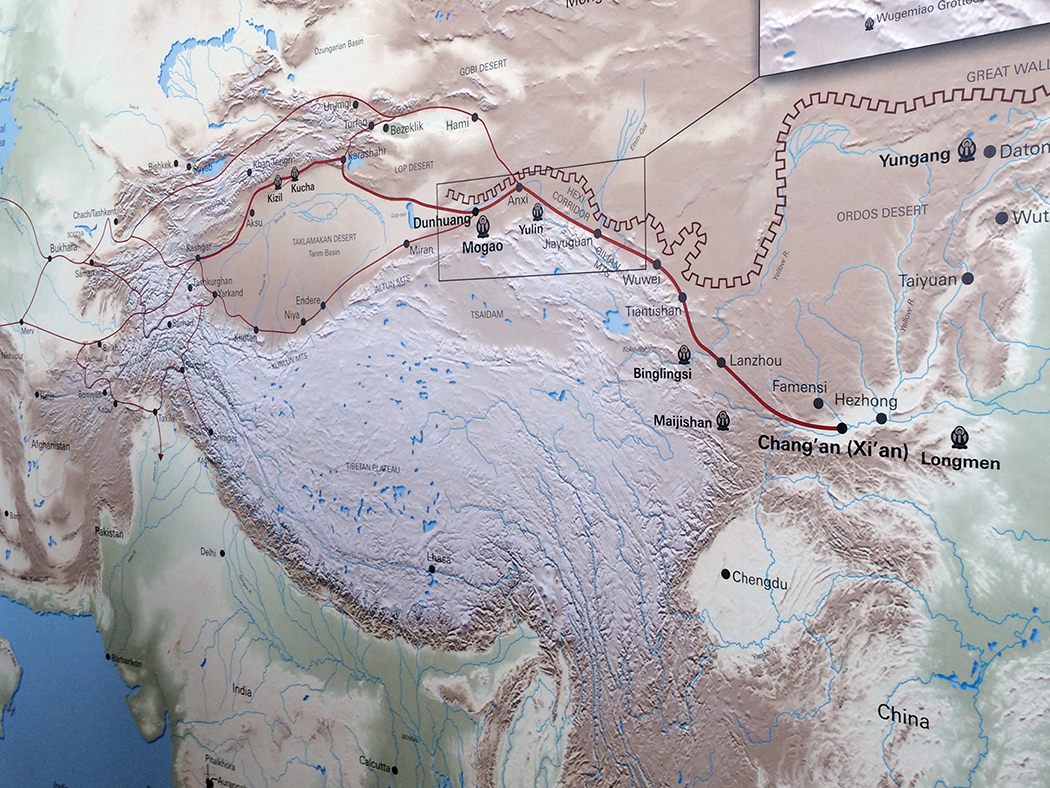

The Silk Road, or Silk Route, was a net- work of trade and cultural transmission routes that were central to cultural interaction through regions of the Asian continent connecting the West and East by linking traders, merchants, pilgrims, monks, soldiers, nomads and urban dwellers from China and India to the Mediterranean Sea during various periods of time.

desert stages of the journey. Branches led north across the steppe and south to India.

Photo: Libby Motika

Reaching its apogee during the Tang dy- nasty (618-907), the Silk Road was the most important pre-modern Eurasian trade route, whereby merchants benefited from the commerce between East and West, and when the Chinese empire welcomed foreign cultures, making it highly cosmopolitan in its urban centers.

The Silk Road could have easily been called the golden road, or the spice road or jeweled road for the variety of goods exchanged, according to Victor Mair, professor of Chinese language at the University of Pennsylvania: carpets, gold, semi-precious stones, fruits and animals from the Mediter- ranean; and from China, bowls made of the thinnest porcelain, bronze ornaments, medicines, paper, rice and tea.

“The major route traveled through the Gansu Corridor in Northwest China, which was like a funnel leading down into central China to Chang’an (Xian—home of the Chinese [terra cotta] soldiers). On the western end, this route eventually split into various trade routes along the edges of the Gobi desert on its journey to India.”

Part trade route and part pilgrimage road, the Silk Road became the conduit for the spread of Buddhism in China from India. Merchants embraced the moral and ethical teachings and supported Buddhist monasteries along the way, and in return the monks gave the merchants lodging as they traveled from city to city. These communities became centers of literacy and culture with well-organized marketplaces, lodging and storage.

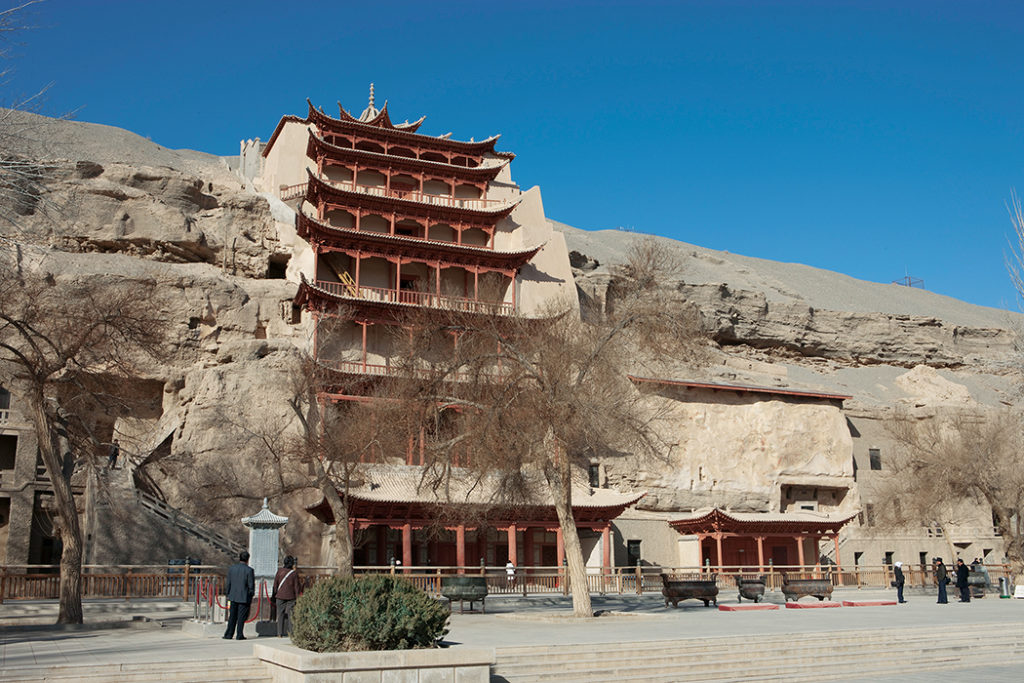

story temple can be seen at the center. Beyond the plateau above the cliff rise the Mingsha Shan—the Dunes of the Singing Sands.

Photo: Sun Zhijun, ©Dunhuang Academy

One such center was the city of Dunhuang, an oasis in Northwest China, and the site of some of the most spectacular Buddhist cave temples on the Silk Road.

In an extensive and ambitious new exhibition, The Getty Center explores the art, environment and conservation of the cave temples of Dunhuang.

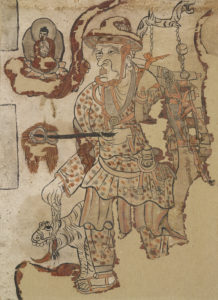

Carved from soft sedimentary rock conglomerate, the caves varied in size, from those accommodating just three people to others able to hold large assemblies, or a 100-ft. Buddha. They were constructed by monks to serve as shrines with funds from donors, often important clergy, local ruling elite, foreign dignitaries as well as Chinese emperors. The caves were elaborately paint- ed with colorful narratives of the Buddha’s life, often used as teaching tools to inform the illiterate about Buddhist beliefs and parables.

The cave temple complex, known as the Mogao Grottoes, was a thriving Buddhist center from the 4th to the 14th centuries, and is considered the most important site. After the Tang dynasty, the site went into a gradual decline and the construction of new caves ceased altogether as Islam had conquered much of Central Asia and the Silk Road was abandoned for trading via sea routes. But there are 472 surviving caves, 2,400 statues and hundreds of thousands of miles of paintings.

Through some 40 objects discovered in 1900 in Cave 17, known as the Library Cave (borrowed for this exhibition from the Brit- ish Museum, the British Library, the Musee

Cuimet and the Bibliotheque nationale de France), we learn the details of life and influences of major cultures that spread throughout the world from travelers on the Silk Road—Greek and Roman via India, Middle EasternandPersian,IndianandChinese.

The exhibit displays manuscripts, paint- ings on silk, embroideries, preparatory sketches and the Diamond Sutra, a sacred Mahayana Buddhist text, dated May 11, 868, and thought to be the world’s oldest dated complete printed book.

Since few of us will visit this World Her- itage Site, the Getty has constructed three full-scale, hand-painted replica caves, filled with Buddhist paintings and sculpture.

These replica caves were created by artists from the Dunhuang Academy of Fine Arts Institute in a time-consuming, step-by-step process. Clay from the riverbed that courses in front of the Mogao site was used for the base for the paintings. To replicate the paintings, artists photographed the original images and then were able to trace and hand paint using traditional pigments and scaled to original sizes.

Each of the three selected caves offers unique features, from painted stories of Buddha’s past lives to the magnificent ceiling in Cave 320 (8th century) teeming with small Buddhas surrounding a central peony motif.

It’s best to study the objects in the Getty Research Institute galleries first in order to understand how the caves were constructed, and most helpful to study the narratives and persons the paintings depict, while learning some basic Buddhist beliefs.

A multimedia gallery presenting a detailed examination of Cave 45, using 3D glasses, heightens the experience. Each of the walls of this High Tang cave is highlighted while the narrator explains the imagery, including the seven-figure sculpture group considered one of the treasures of Mogao.

Conservation of the site and its art is a cornerstone of the exhibition. For the past 25 years, the Getty Conservation Institute and the Dunhuang Academy have been working on site conservation and environmental monitoring, using Cave 85 as a test case for experimenting with effective ways for conservation and treatment of deteriorating walls.

The shrine in Cave 85, a large late Tang dynasty grotto commissioned in 860, is decorated with life-size portraits of donors and high officials and conveys insights into many aspects of life in this remote part of China.

In addition to using their scientific skills to stabilize the caves, conservationists have been addressing the impact of tourism, resulting in a visitor management and reservation system.

The 21st-century visitor has much to learn from the ancient Chinese documents discovered in the Library Cave, including volumes of information on science and technology: a new type of plow, the use of stirrups, lunar calendars, classical herbal medicine and acupuncture, celestial maps, printing and distilling.

Visitors to Dunhuang learn about the history and art of the cave temples through digital and film representations, before touring the caves. But closer to home, the cave temples in the Getty exhibition offer an experience that gives us a palpable feel of the Mogao.

The exhibition runs through September 4. Visit getty.edu or call (310) 440-7360.

By Libby Motika

Palisades News Contributor

You must be logged in to post a comment.