By Libby Motika

Palisades News Contributor

While Ethel Fisher was enjoying the camaraderie of the New York art scene in the early 1960s, exploring the outer limits of what she dubbed abstract impressionism, the London artists in the current exhibition at the Getty Museum were defiantly rejecting abstraction, insistent on the validity of the concrete reality they saw around them—the city, landscape and people, albeit transformed by imagination.

A well-regarded painter who has lived in Pacific Palisades since the early 1970s, Fisher flourished in New York in the exuberant rules-breaking ‘60s. She studied at the Art Students League, whose instructors and students over its long history include famous artists who have shaped the vocabulary of art worldwide, from Thomas Hart Benton to Roy Lichtenstein. Her work has been featured in a number of solo exhibitions in cities around the country and in Havana, Cuba. Ethel and her husband, the late Seymour Kott, thrived in the artists’ community at what was a very exciting time in New York.

At the same time, from the 1940s through the 1980s, a group of London-based painters resisted the abstraction, minimalism and conceptualism that dominated contemporary art at the time, instead focusing on figurative works. The leaders of this movement, known as the School of London, included Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud, Leon Kossoff, Michael Andrews, Frank Auerbach and R.B. Kitaj.

On view through Nov. 13, “London Calling: Bacon, Freud, Kossoff, Andrews, Auerbach and Kitaj” includes 80 paintings, drawings and prints.

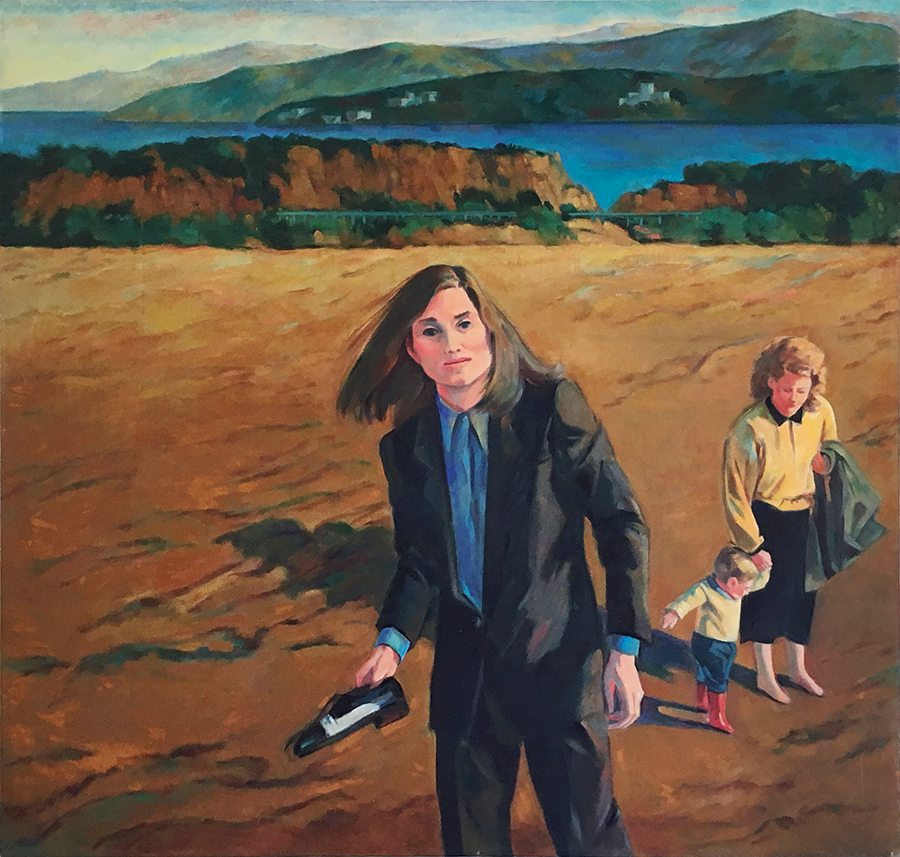

The bridge between these two art worlds, separated by the great Pond, was Ethel’s daughter Sandra Fisher, who was Kitaj’s wife and muse. She had met him while working as Ken Tyler’s assistant at the print atelier Gemini Ltd. in Los Angeles, where Kitaj’s graphic works were produced. Later when she moved to London to paint, the two reconnected.

More than the son-in-law/mother-in-law relationship, Kitaj and Ethel related painter to painter, Ethel says. “He knew a lot of the artists I knew. I met Kossoff and Auerbach, both of whom are still drawing every morning and painting every afternoon. I’d stay with him and Sandra in their old Victorian in Chelsea, and when Kitaj returned to Los Angeles after living many years in London, he and David Hockney visited with us here in the Palisades.”

Kitaj, born in 1932, was the youngest of the so-called London School, the moniker he coined in 1976.

Working with the Tate of London, the Getty exhibition displays the radical ap- proaches to figure and landscape pioneered by these artists.

“The group bonded over the fact that they were still working in what was considered ‘Old Hat,’ while moving forward to the next level in those particular idioms,” says Julian Brooks, curator of drawings at the Getty, who along with Getty Director Timothy Potts and Elena Crippa, curator of Modern and Contemporary British art at Tate, orchestrated this show.

“It was more than just representations,” Brooks continues. “They were trying to capture the essence of the picture.”

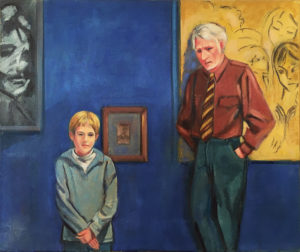

These artists, all men, knew one another and respected one another’s work. Tellingly, Kitaj’s painting of his wedding to Sandra in 1983 depicts how these painters were linked by both friendship and shared artistic concerns. Hockney was his best man and Freud and Kossoff are shown attending the ceremony.

“Another tradition these painters share is a regard for the Old Masters and for drawing,” Brooks says. “Each found common threads in the 17th-century portraits by Rembrandt, and 18th-century Constable landscapes. The National Gallery was a focal point for all of them, where they would go to paint, and where Kossoff does to this day.”

For these artists, the work was arduous, often disappointing as they searched to uncover the essence, the truth of the art.

“Auerbach was known to add layer upon layer of paint to the same canvas day after day until in 1960 he had a breakthrough and felt he had the confidence to scrape it away and start again,”Brooks says.“But even then, he felt there was a little bit of what had been remaining on the panel and in his mind. At some point, he felt he was finished.

“Freud worked so long on one painting, many for months and months, there is that sense of striving for perfection and not quite sure that he had ever found it. “Kitaj said he didn’t regard any of his paintings as finished, and Bacon certainly destroyed many of his canvases, burned many of them. It was a sense of not letting things out in the world.”

Not all of these men were of English birth; Freud and Auerbach, both born in Berlin, moved to London as children to escape Nazism. Kitaj’s Russian and Yiddish-speaking maternal grandparents helped raise him in the “bleak, but loving industrial northern Cleveland.” These Jewish, Socialist roots (his grandfather read the Yiddish Daily Forward every day) influenced the young man, whose writing and later painting tended toward the ancient Jewish tradition of ceremony.

After sailing the seven seas, as Hockney characterized Kitaj’s stint as a merchant seaman and in the U.S. Army in Europe, he moved to England in 1959 to study at Oxford and the Royal College of Art and met others of the School of London.

Kitaj had a significant influence on British pop art, with his figurative paintings featuring areas of bright color, economic use of line and overlapping planes that made them resemble collages, but eschewing most abstraction and modernism.

He staged a major exhibition at Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1965, and a retrospective at the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C. in 1981.

Unexpectedly, a second retrospective in 1994 was savaged by the London critics and changed the course of Kitaj’s life. The real casualty of this battle—the “Tate War” in Kitaj’s eyes—was his wife, who died of a brain aneurysm at 47, two weeks after his Tate show opened, and whose death the painter blamed directly on the shock of his very public critical humiliation.

The fallout led Kitaj’s self-imposed exile from London back to Los Angeles with his 10-year-old son, Max.

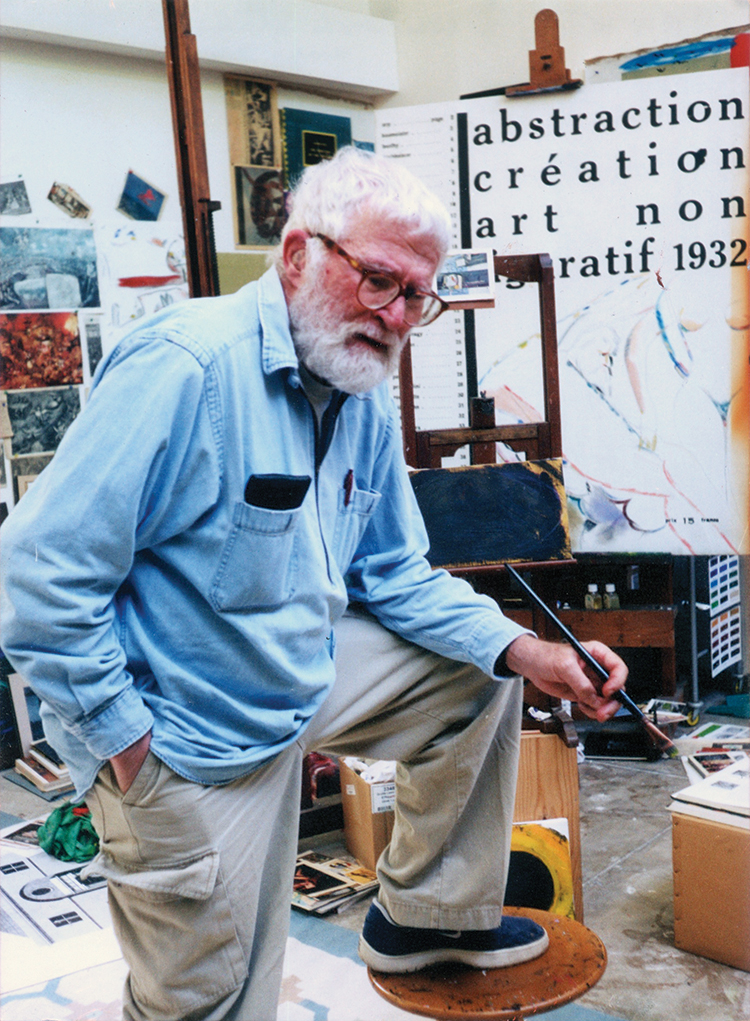

Once back here, Kitaj fell into a pattern. Living in Westwood, he would walk to the Coffee Bean on Gayley, his favorite café, where he would write notes, manifestos and an unfinished autobiography on yellow legal pads.

Ethel Fisher recalls that Kitaj dedicated different rooms in his house for various projects. “His living room was for draw- ing, and he built a studio in the garage and painted it yellow, after Van Gogh’s yellow.

“His policy was not to be in business before 4 p.m.” Fisher says. He and Max would stop by her house every week or two. “We both liked film, action movies mostly, like Raiders of the Lost Ark and The French Connection. He loved the stars’ hats and asked me that if I ever came across an Indiana Jones fedora or Hackman’s pork-pie hat, would I buy it for him?”

The “Tate War” and Sandra’s death became a central theme for Kitaj’s later works: he often depicted himself and Sandra as an- gels. He was elected to the Royal Academy in 1991, the first American to join the Academy since John Singer Sargent.

A diary entry attached to a 2004 self-portrait of the artist staring at the viewer from under a baseball read: “Mid Aug. 05. Here I am again, after a year or so, still alive, still an irritant. I have Parkinson’s disease but it’s OK so far. I love my cane, draw, study, write in my Coffee Bean café every day.”

One of Kitaj’s last diary entries seemingly announced his imminent intention: “Failure, failure as always.” He was found dead at 74 at his home in October 2007.

Photo: Ethel Fisher

You must be logged in to post a comment.