By Jack Ross

Staff Writer

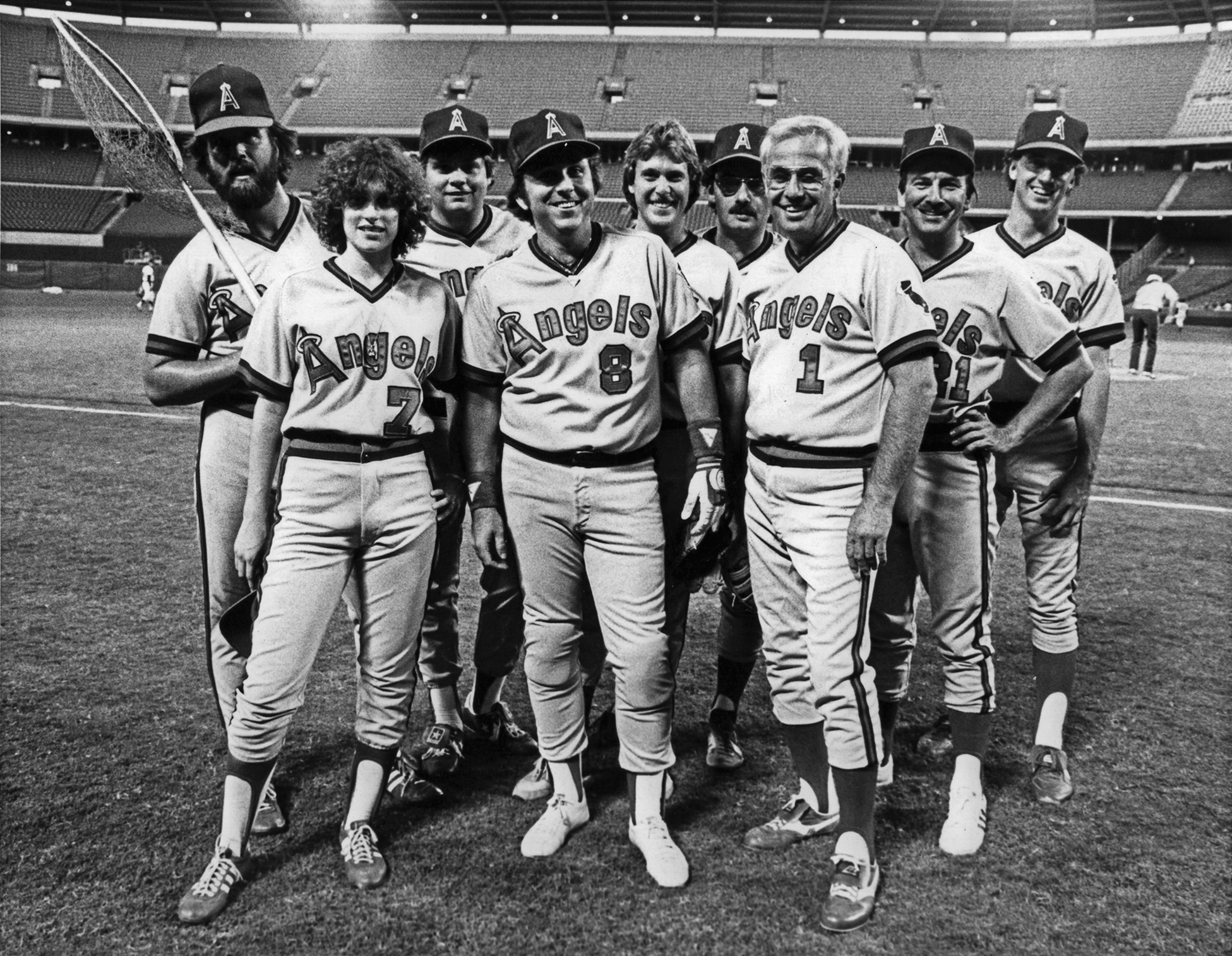

When Lisa Nehus (now Saxon) became one of the first female reporters to cover major league sports in the 1980s, sexual harassment and gender discrimination were not yet a part of the American vernacular.

“The road I traveled was not easy,” says Saxon, who covered baseball, football (including the Super Bowl) and UCLA basketball during her 22-year newspaper career. “We had to fight just to get locker room access. And once we had access, it was open season.”

Early in Saxon’s career, in locker rooms everywhere, players yelled, spit and threw jock-straps at her, exposing themselves, and even masturbated in front of her.

Saxon responded by quickly developing a thick skin. And sharp wit.

Players would open their towels and loudly declare, “Have you ever seen anything like this before?” Saxon’s reply: “Yeah, it looks like a penis, only smaller than what I’ve seen before. Put it away.”

Another favorite: a guard would stop her at the door, and state, ‘No Women Allowed’ despite Saxon’s clearly visible media credential. Her rebuttal: “The press pass says, ‘Admit Bearer,’ not ‘Admit Bearer with Penis.’”

In her first days on the Angels beat (in 1982, as the back-up writer for the L.A. Daily News), manager Gene Mauch made his unhappiness about Saxon clearly known: “‘I can’t keep you out of my clubhouse, but if you come into my office, I’m not talking.’ I put my hand out, and he turned on his heels and ran into center field. I just smiled and said, ‘Nice to meet you, too, Gene.’”

“Most of the reporters told me not to go in his office,” Saxon says. “They felt it would compromise their ability to do their jobs. And for a while—I was only 22 years old— I did what they wanted.” But she knew it wasn’t right—she was missing out on valuable post-game quotes—and the next season, after Mauch was replaced by John McNamara, she went into the manager’s office.

McNamara was “like an uncle,” Saxon says, a constant source of strength, teaching and kindness and made sure she was treated fairly.

Saxon was one of just three women covering the majors full-time in 1983, and when she grappled with quitting amidst deep frustrations and the day-to-day disrespect on the road, McNamara offered words of encouragement: “If you’re tired of it, that’s one thing. But you cannot let someone else decide what you’re going to do with your life.”

His message kept Saxon focused on her love of baseball, reporting and writing. But in 1984, when she began covering the Dodgers, a new challenge emerged. The American League allowed women in team clubhouses, but National League teams decided on a team-by-team basis, meaning Saxon never knew if she would be allowed in on any given night.

During the World Series in Cincinnati, Saxon recalls: “I got into the clubhouse by blowing by the guard who tried to stop me, even though I had a credential. I was talking to a player when someone put their hands on me and forced me out. At one point, both of my feet were off the ground.

“Once I got upstairs to the press box, the Reds’ PR director, Jim Ferguson, started screaming at me that I could not go into the clubhouse. While Ferguson was yelling, a dog was running around the field. I looked at the message board, where there was a statement about dogs joining the Cincinnati police force the same year women were admitted. I pointed to the board and told Ferguson, ‘I get it. In Cincinnati, women are treated like dogs.’ Ferguson was not amused. He ordered an intern to follow me around Riverfront Stadium for the rest of the Series.”

“I was the only woman in the press box who wasn’t served food. I asked my own newspaper to help me, but I was told that I was a ‘big girl’ and could handle it. I wasn’t angry; I was frustrated. I was 24 years old and fighting Major League Baseball on my own—and also dealing with some passive-aggressive copy editors at the Daily News, who repeatedly pointed out that they didn’t think I was doing a good job. In 1984, I worked 98 consecutive days, got one day off, and worked 76 more consecutive days.”

Saxon was happy about returning to the Angels in 1985, and stayed until August 1987, when she began covering the Raiders for the Long Beach Press-Enterprise. Three years later she moved to the Riverside Press-Enterprise and covered college sports (plus some major news events such as the L.A. Riots and the Northridge earthquake aftermath) until she fell victim to staff cutbacks in 2001.

Long before her fight for equality hit male-dominated locker rooms, Saxon knew what it meant to experience discrimination. At age 13, she won a Pitch, Hit and Run competition against a field of boys (and one other girl). One mother, whose son finished second, pointed out the application specified the contest was for boys only. Lisa didn’t get to advance to the next round, but no matter. Her unwavering goal was to cover baseball, not play it (though she did own two gloves, paid for with Blue Chip stamps). At Cal State Northridge, Saxon secured a scorekeeping job on Bob Hiegert’s baseball team, and volunteered on the sports desk at the Daily News. After two years—with only two journalism classes under her belt—she was hired full-time, which meant working at night and taking classes by day until she graduated.

Soon she was on the Angels beat. “People tell me I was a pioneer,” Saxon says. “Really, I was just a naive, enthusiastic young woman, doing what I loved. I never un- derstood the pioneer part. It really wasn’t until I left journalism that I had a clearer view of what I accomplished.”

Recently, Saxon was nominated for a lifetime achievement award from the National Association of Women in Sports Media. And during a visit to the Anaheim press box this season, she met a female reporter from Palm Springs who told her, “You’re sitting here and I’m standing on your shoulders.”

Saxon has found a second satisfying ca- reer as a teacher, having joined the faculty at Palisades High School in 2006. She taught English until three years ago, when she took over the journalism department. The student newspaper, The Tideline, is now published as a color magazine, and this year the staff received a first-place ranking in the annual newspaper evaluation sponsored by Quill & Scroll, the journalism honor society.

Saxon and her husband Reed, a Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer for the Associated Press, live only a few blocks west of PaliHi with their three cats, Perry, Sammy and Milo. They met in 1983 in the press box (naturally!) at an Angels-Rangers game, married in 1986 and moved to the Palisades a year later.

You must be logged in to post a comment.