By Laurel Busby

Staff Writer

Photos by Shelby Pascoe

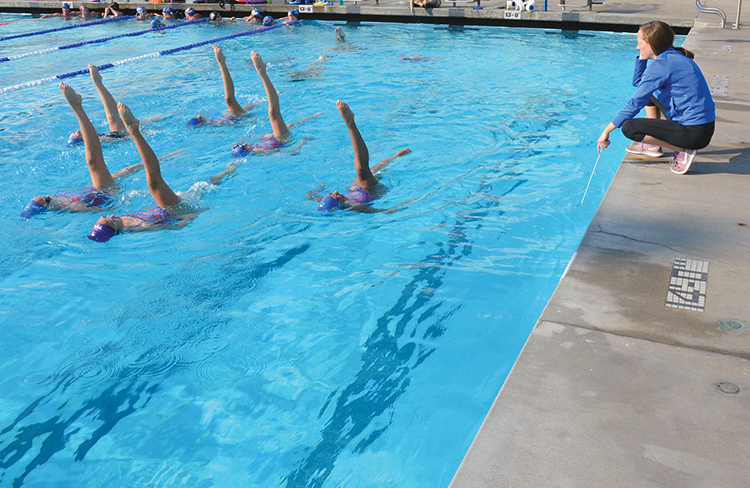

Like upside-down Rockettes, the team strives to kick their legs in unison, while the rest of their bodies hover almost invisibly underneath them.

After an array of kicks, they pop to the surface, continuing to dance together with flips, floats and other synchronized swimming maneuvers. Sometimes they dance to music, which is audible even underwater, and other times, a coach sits at the edge of the Palisades High pool tapping a stick against the side, so the girls can properly time their movements to its beats.

Even when they aren’t performing a routine, the Westside Aquatics team members are moving, treading water while they listen to a coach’s instructions or chatting among themselves. They look happy and comfortable, yet also focused when they begin their choreography.

Mia Sim, 12, a Paul Revere seventh grader and a member of the club’s Junior Olympic squad, has been part of the team for two years and said she treasures the sport “because of how satisfactory it is. For example, when you finally perform for the judges and hit a hard move just right, or even looking back at your routine and seeing everyone synchronized at one point makes all the pain, soreness, effort and hard work worth it.”

Other synchro swimmers, who can begin participating in the Westside Aquatics introductory splash program as young as five years old, revel in the joy of learning tricks in the water.

For example, pre-team member Mia Mozenter, 10, said, “It’s really fun because we get to dance underwater and do all these fun moves.”

Her mother, Tammy, said they happened onto the sport when Mia was taking swimming lessons and synchro coach Valerie Williams suggested that Mia give it a try. The Pacific Palisades family knew nothing about synchronized swimming, so they checked it out online and thought it looked intriguing.

“And she loves it, loves it,” Tammy said. “She’s really motivated. She loves coming. . . . She’s never liked anything as much as she likes this.”

Head coach Williams, who also is an assistant coach for the U.S. national team, found the sport as a child through a city recreational program. She later moved onto a club team and transitioned to coaching after a car accident.

“The combination of artistry with athleticism” appealed to her, Williams said.“ I really like combining music and movement—in the water is such a completely different ex- perience than on land as a dance. . . . The underwater world is very cool.”

In practices, the team, which trains together three times each week, works both on land and in the pool to develop strength, endurance, flexibility and artistry. The 30 minutes of land training might include jumping jacks, resistance bands, pushups, ballet kicks, yoga and acrobatic skills, such as bridges and handstands.

Pool work could feature both regular laps and synchronized swimming exercises like swimming underwater and holding your breath or doing laps using the eggbeater, which is a specialized way to tread water. Sculling, which is a way to use your arms to support yourself, would also be practiced.

Work on routines is also a central part of practice time. For both the novice/intermediate and the Junior Olympic groups, competition routines include choreography moving across a large swath of the pool.In addition, the swimmers might train separately for solos or duets. At the competitions, scoring is a bit complicated.

“The swimmers perform four figures individually and those scores are added to their routine score,” Williams said. “With a system similar to other artistic sports, there is a panel of judges giving scores on a 10.0 scale for execution, difficulty and artistic impression.” The judges’ scores are combined for a total between 1-100. The top team in the world, which is currently the Russian team, might score as high as 98, while other elite teams will have scores ranging from the 80s to 90s, Williams said. Young teams’ scores will typically range from the 40s to the 60s, depending on their level.

As the Westside Aquatics team has grown from three swimmers in 2014 to 16 competitors today, more coaching has been added, including French Olympian Cinthia Bouhier; Jane Kok, who swam for Ohio State’s team; and Chloe Larouche, who swam for the Canadian national team. Some of the coaches also still perform as professionals for the company Aquabatix.

First called water ballet, the sport was initially a male-only event, but in the 20th century, it flipped into a mostly female sport with men in the U.S. either banned from joining women in many competitions or as of 1941 required to compete separately by the Amateur Athletic Union, which caused male participation to dwindle. In the U.S., men were again allowed to compete with women on the amateur level in 1978. However, men have yet be allowed to compete in the Olympics, which first offered the sport in 1984.

The local Westside Aquatics team is all girls at the moment, with 16 swimmers divided among the pre-team, novice/intermediate team and Junior Olympic squad, while another 12 girls have experimented with the introductory splash program over the past year.

Coach Larouche, who from 7 to 18 years old trained up to 40 hours a week as a synchronized swimmer, said that the sport tends to appeal to those who give it a try.

“It’s the best sport in the world,” she said. “We’re made of 80 percent water, so you know if you put music on and your body is in the water, there’s nothing better.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.