By Laurie Rosenthal

Staff Writer

Photos courtesy of The Broad

We live in an era of turnover, of constantly looking for the next big thing, of instant fame. Often today’s biggest names disappear tomorrow.

Fortunately, there are some names—and some artists—who rise above the din and become a part of history because their contribution is so consequential and influential.

Centuries after their deaths, Michelangelo and Rembrandt remain among the most popular and recognized names in the art world. And so it will be with American painter and sculptor Jasper Johns, whose work will likely be revered for centuries to come.

The Broad’s presentation of Johns, 87, is the most comprehensive exhibit of his work to be seen in Southern California in over 50 years. He was 34 when the Pasadena Museum of Art mounted a large exhibition of his early work.

“Something Resembling Truth” is on view through May 13. The title comes from a Johns quote from the mid-aughts: “Yet, one hopes for something resembling truth, some sense of life, even of grace, to flicker, at least, in the work.”

Curated in conjunction with the Royal Academy of Arts in London, the exhibit is an exhaustive look at Johns’ career. The Broad’s Director Joanne Heyler told a crowd of assembled journalists that “an exhibition of this magnitude takes precision planning, experienced perspective and above all, long hours.”

The exhibit is spread out over five galleries, but only seven of the 127 pieces belong to The Broad. The rest are borrowed from dozens of institutions and private lenders from around the globe. Usually The Broad is the lender, not the borrower, Heyler said. “It was gratifying to be trusted” with so many of Johns’ works.

One of the most revered artists of the 20th century, Johns, who was part of the 1950’s New York art scene with his contemporaries such as Robert Rauschenberg, brought a new narrative and altered established notions of what qualifies as art.

The News spoke to Associate Curator Ed Schad about his thoughts on why people are still drawn to Johns’ work, and why it is so timeless.

“It’s a little hard to figure. Everybody is different. I think they’re extraordinary objects when you walk into the gallery. They are so exquisitely rendered, and so full of energy and life as objects that they sort of beg for closer inspection,” Schad said.

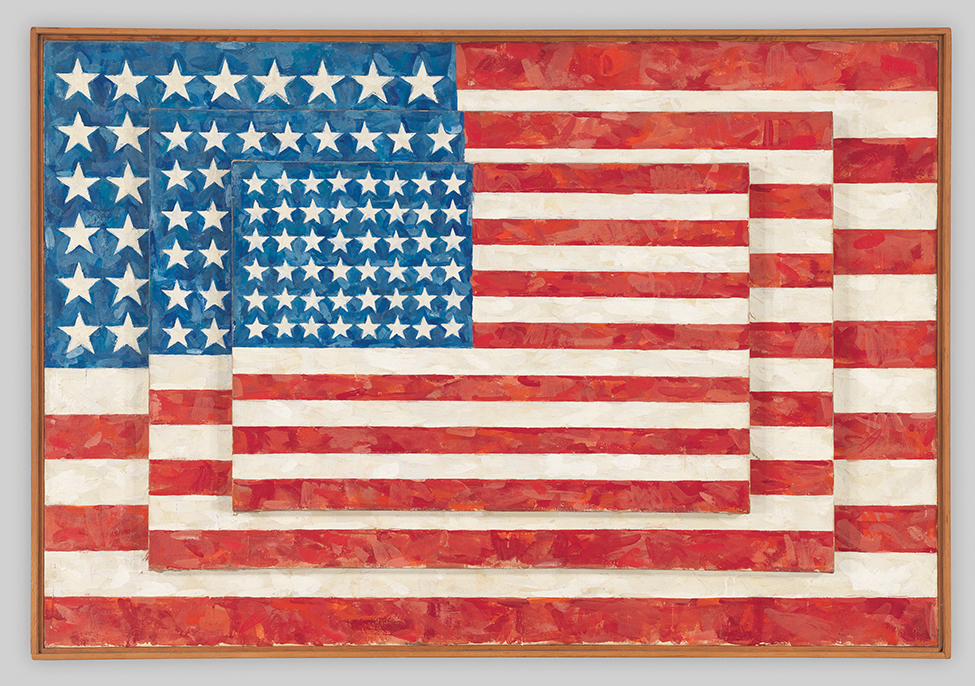

Flags, featured predominantly in Jasper Johns’ work since the 1950s, take up the first gallery.

“I am not sure that the flag at the beginning meant something political,” Schad said. “He has said that was not his intention. It was more his intention to get into the mechanics of seeing, and why we see, what we see.”

“Now, 10 years later, 20 years later, 30 years later, our government evolves, we evolve, our relationship to things evolve. And so, naturally, our perception of the flag will change. I think that’s something that’s built in the work.

“A person who comes to our galleries and sees the American flag will have to have their own reckoning with it,” Schad continued. “One thing I do know for sure is the experience is a slow one, a deep one. It’s focused on what that image as both object and symbol is doing right in front of you on canvas.”

©Jasper Johns/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

In one image, the American flag is re-imagined with green and black stripes, black stars and an orange background. Another flag features a gray background, gray stars and gray stripes. One small flag has 64 stars. According to Schad, that happened simply because Johns “lost track of the stars and ended up with too many.”

Perhaps the pièce de résistance of the flag section of the exhibit is “Three Flags,” created in 1958 and owned by the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. The museum paid $1 million for the painting in 1980, at the time the highest price ever paid for a piece by a living artist. “Three Flags,” which turns 50 this year, is both modern and timeless—as relevant today as it was 50 years ago or (hopefully) will be in 50 years.

Seldom loaned out, the traditional 48-star American flag is mounted on a larger flag, which in turn is mounted on an even larger flag. The Whitney’s website states that in “Three Flags” Johns “explores the boundary between abstraction and representation.”

As prevalent as the flag has been in Johns’ career, there are many other influences, and they are abundantly represented at The Broad.

False Start is a collection of colors and mismatched words. For example, the color yellow is painted in yellow, with the word white painted over it in red. It’s almost a brain quiz, testing one’s ability to read what color is written while simultaneously thinking what the color painted under the word says.

©Jasper Johns/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Another subject that Johns has worked with frequently over the years is numbers, and they are represented in the exhibit in different mediums, including bronze and graphite. In many paintings, numbers are painted over each other, with one color on top of another color on top of yet another color, while in others there is a repetition of numbers, a technique Johns repeats with letters.

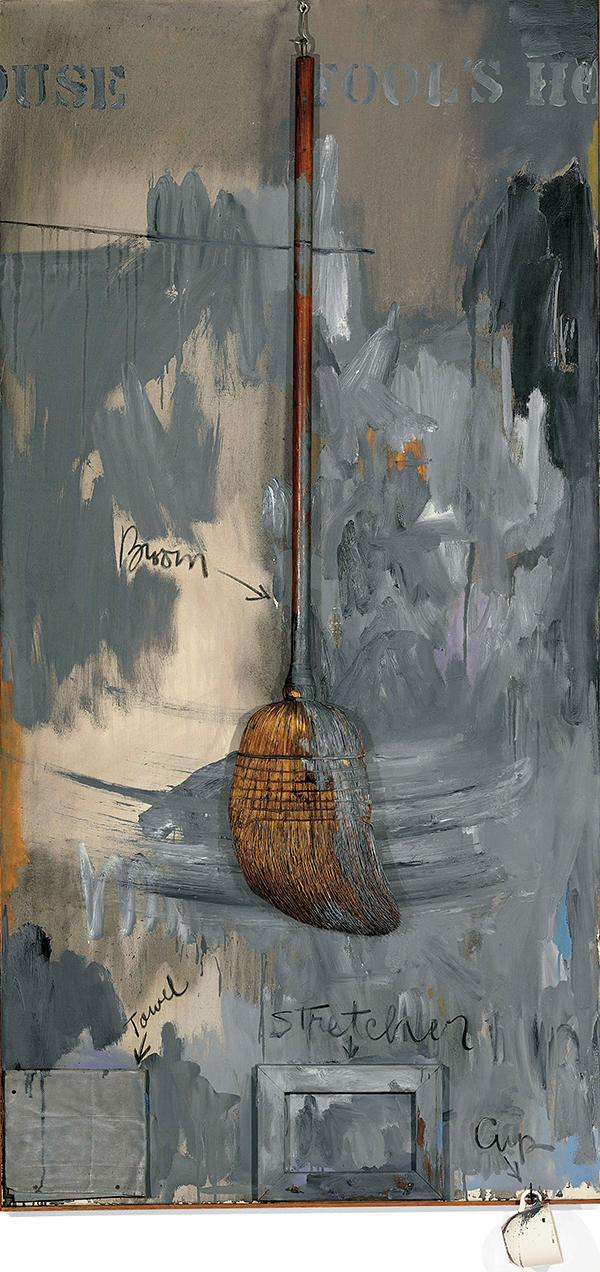

Johns is also known for his crosshatch images, collages, encaustic (beeswax) paintings and use of words in his work.

“One of the extraordinary things about Johns is that he has the motifs that arise over six decades,” Schad said.

“It’s not only a matter of the motifs, but sometimes of the marks themselves that can take on different meanings, and sort of evolve with the weather of his life and our lives.”

Johns continues to live and work on his 170-acre estate in Sharon, Connecticut, which, after his passing, will be turned into a retreat for a variety of creative individuals, including visual artists, writers and musicians.

“Something Resembling Truth” will be on view through May 13. For more information about the exhibit and special programs, go to www.thebroad.org.

©Jasper Johns/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

You must be logged in to post a comment.