By Libby Motika

Palisades News Contributor

In the early 1800s, an Indian girl spent 18 years alone on the desolate island of San Nicholas, using her wit and the wisdom of her ancestors to sustain body and spirit.

At the time of the European contact, two distinct ethnic groups occupied the Channel Islands: the Chumash on the Northern Islands and the Tongva on the Southern Islands, including San Nicholas.

After first suffering slaughter by Native Alaskan otter hunters working for a Russian-American company, and then removed to the mainland by the Franciscan padres, the Tongva islanders disappeared.

Except the Indian Girl, who was inadvertently left stranded on San Nicholas for almost two decades. Ultimately rescued, Juana Maria, so named by the padres, lived for just a short time on the mainland before succumbing to a fatal illness. She died in 1853.

The story of Juana Maria serves as a synopsis of Tongva history. Her survival on the island depended on her ingenuity in providing for herself. She built a hut, partially constructed of whalebones; she fashioned a skirt made of cormorant feathers; and she contrived all her domestic essentials, including baskets and bone needles.

The current exhibit at the Santa Monica History Museum explores the history and cultural influence of the Tongva and the actions of the tribe to recognize and preserve their presence in Southern California.

Photo: Lesly Hall Photography

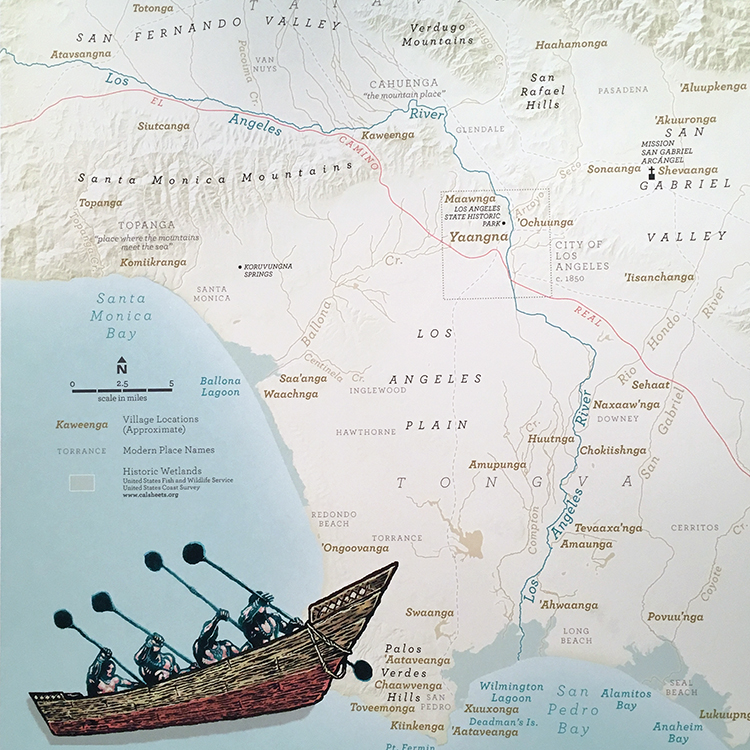

The Tongva inhabited all of Los Angeles County, the northern parts of Orange County, and the four southern Channel Islands, including San Nicholas, Santa Barbara, Santa Catalina and San Clemente.

They were the people who canoed out to greet Spanish explorer Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo off the shores of Santa Catalina and San Pedro in 1542. He declined their invitation to come ashore and visit.

By the time of the first Spanish settlers in 1781, an estimated 5,000 Tongva lived in some 31 known villages with as many as 400 to 500 huts.

Each village was identified by family lineages of extended families. Many contemporary place names derive from Tongva, such as Topanga, Cahuenga, Tujunga and Moomat Ahiko Way in Santa Monica.

A number of Tongva sites on the Westside bear testimony to those who inhabited our land long before us.

The Kuruvungna Springs, or a place we stop in the sun, on the University High School campus, is the site of Tongva burial groups. A 150-year-old Mexican cypress, known as the Abue Wete Tree, was planted by the Portola expeditions as a water marker. The Gabrielino Tongva Springs Foundation opens it to visitors each month.

Los Liones Canyon is a place of significance in Tongva oral histories. It was threatened with development in the 1990s when members made a successful case for its preservation.

The Tongva Park in Santa Monica, opposite the Santa Monica Pier, is a symbolic nod to Santa Monica’s earliest inhabitants, whose descendants supported the naming. Planned to preserve existing trees, it includes native grasses and succulents.

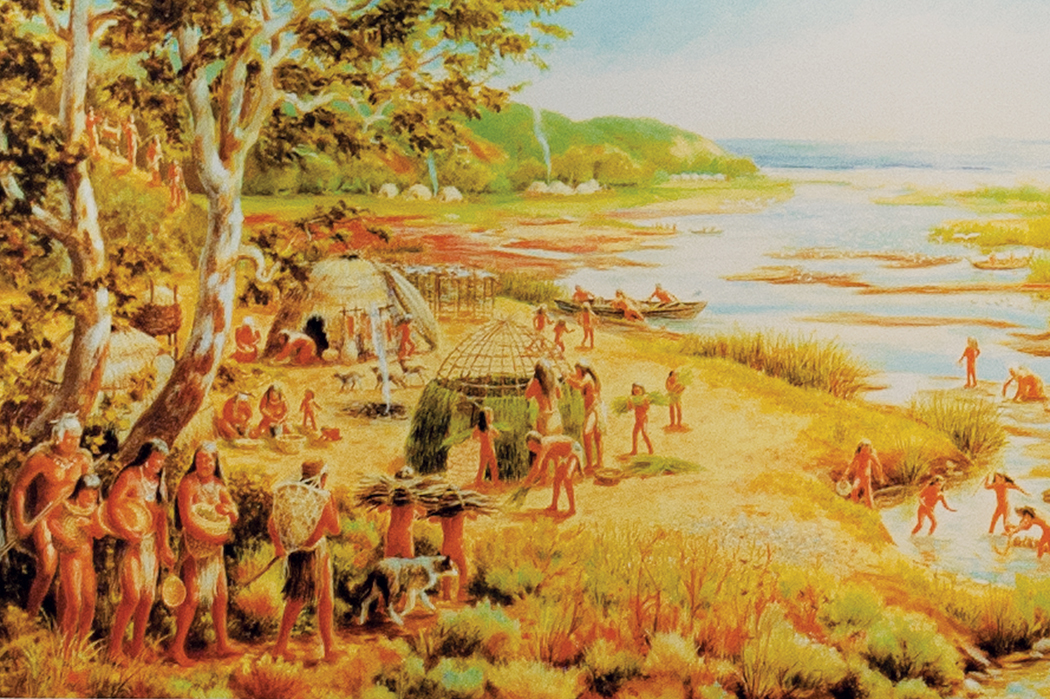

Precontact Tongva were hunter-gathers. Each family in a village had its own leader, who took care of the sacred objects belonging to the village, settled disputes and collected taxes.

In the villages near the coast, the main food came from the sea. Away from the coast in the foothills, acorns, piñon nuts, sage, berries and other plants provided nutrition.

Interaction among the villages was common, leading to intermarriage and political alliances. Steatite, also known as soapstone, was the primary trade item for the Tongva. They also supplied shell beads, dried fish and sea-otter skins to people living away from the ocean, in exchange for acorns, seeds, obsidian and deerskins.

The Tongva believed in a religion named after their creator: Chingichnish.

Women and men could be shamans, the religious leaders and healers of the tribe. It was believed that they had special powers to heal the sick and to change their shape from human to animal.

By the mid-19th century, with the Mission San Gabriel fully established, well over 25,000 baptisms had been conducted, which led to the disappearance of the pre-Christian religious beliefs and mythology. The People of the Earth, lost to assimilation into Spanish and Mexican culture, were rechristened Gabrielinos because of their close association with the Mission San Gabriel.

The Tongva language was on the brink of extinction by 1900, leaving only fragmentary records of the indigenous language and culture.

But fortunately, the Tongva were storytellers. Passed down through the generations, the stories taught lessons, customs and beliefs and how to understand the natural world.

Photo: Lesly Hall Photography

For Tongva tribal elder Julia Bogany, stories not only have been guides to her own identity, but also as primers in teaching the next generation. She takes great comfort in her 12-year-old great-granddaughter Marissa Aranda, who has shown an interest in her culture and looks to be the vehicle carrying the culture into the next generations.

“Stories of six of my ancestor women are powerful to me and have empowered my life and I hope to pass on to Marissa,” Bogany said in an interview with theNews.

An educator and cultural affairs officer for the Gabrielino-Tongva band of mission Indians, Bogany has devoted decades on awakening the world to the existence of her people. She and other Tongva educators consult with schools, cultural centers and museums to correct misinformation about the tribe.

At a two-day workshop in August 2017, co-sponsored by the UCLA American Indian Center, the Cal State Dominguez Hills History Project and the UCLA History Geography Project, Tongva educators gathered with two dozen elementary school teachers to increase their understanding of the Tongva community and history. The goal was to develop a curriculum for third graders.

Bogany takes special pride in changing the narrative of the Tongva at the San Gabriel Mission, where her ancestors were brutally enslaved and subjected to starvation and disease.

“It took three bishops to get them to have an offensive sign removed,” Bogany said. “It read: ‘The Spanish came with beautiful horses but had to deal with the Red Skins.’ The museum is doing something really powerful because if the government doesn’t recognize us, they should, because WE WERE THERE.”

The Gabrielino-Tongva are one of two state-recognized tribes and the best documented tribe in the state without federal recognition.

“People of the Earth: Life and Culture of the Tongva” continues until May 5 at the Santa Monica History Museum, 1350 Seventh St.

You must be logged in to post a comment.