For some people, baseball is a bewildering mass of facts, rules and statistics, but for far more Americans the game is a hallowed tradition, a rite of passage.

For some people, baseball is a bewildering mass of facts, rules and statistics, but for far more Americans the game is a hallowed tradition, a rite of passage.

“Only the people who think baseball is dull are dull,” said Hall of Fame sportswriter Shirley Povich, whose colorful commentary in the Washington Post for over 30 years challenged anybody to find baseball boring.

When Don Larsen pitched his perfect game in the 1956 World Series, Povich wrote: “The million-to-one shot came in. Hell froze over. A month of Sundays hit the calendar. Don Larsen pitched a no-hit no-run no-man-reach first base in a World Series.”

Baseball, whether played on a dirt lot or in a domed stadium, still holds a multi-generation, spring-to-autumn grip on this country, despite inroads by football and basketball.

Currently, 150 years after one of the first professional players, Lipman Pike, rose to prominence playing for the Philadelphia Athletics, the Skirball Cultural Center is featuring an exhibition, “Chasing Dreams: Baseball and Becoming American,” that focuses on the game and its place in American social and cultural history.

“Football may be more of an obsession in America, but even today when it comes to the World Series, the world is focused on baseball,” said Skirball Museum Director Robert Kirschner in his introduction to the exhibition, on view through August.

“Chasing Dreams” follows a loose chronicle of the history of baseball, while in a companion exhibition, “The Unauthorized History of Baseball in 100-Odd Paintings,” artist Ben Sakoguchi’s colorful and provocative paintings focus on the intersection of sport, identity, race and ethnicity.

“Chasing Dreams” follows a loose chronicle of the history of baseball, while in a companion exhibition, “The Unauthorized History of Baseball in 100-Odd Paintings,” artist Ben Sakoguchi’s colorful and provocative paintings focus on the intersection of sport, identity, race and ethnicity.

Baseball has always served as the lingua franca for many different immigrant groups as they have strived to assimilate and become American. While the exhibition does touch on the Chinese and Hispanic embrace of the sport, the Skirball emphasizes the Jewish experience.

“From the field to the front office, Jews have been vital to America’s game,” says Skirball Chief Curator Erin Clancey.

By the 1920s, Jews comprised one-third of the population of New York. There was a big push to attract them to the ballpark through not only advertising, but also by players like Andy Cohen, a second baseman for the New York Giants in the late ‘20s. Unlike five other Cohens who preceded him and Anglicized their last names, Andy retained his name despite pressure to change it. “Being a Jew made me stand out,” he said.

Another exemplary player, Hank Greenberg, a superstar for the Detroit Tigers in the 1930s and ‘40s, was the first Jewish major league Hall of Famer, who honored his heritage by refusing to play on Yom Kippur in a decisive late-season game in 1934. While there is no shortage of remarkable players renowned for their skill, there are others whose integrity, and bravery, changed the culture of the game forever.

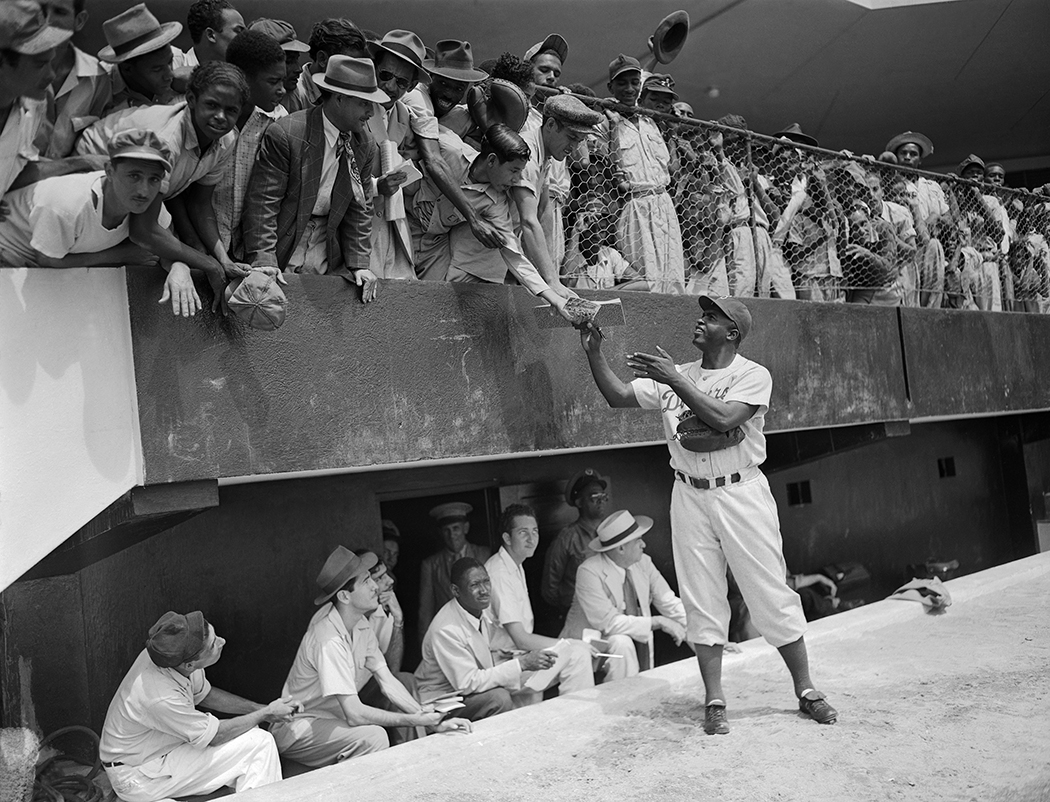

Greenberg endured battering anti-Semitism, and Jackie Robinson, the first African American to play in the major leagues in the modern era, suffered racist vitriol from teammates and the public alike. Joe DiMaggio’s parents were among the thousands of German, Japanese and Italian immigrants classified as “enemy aliens” by the government after Pearl Harbor was bombed by Japan.

Greenberg endured battering anti-Semitism, and Jackie Robinson, the first African American to play in the major leagues in the modern era, suffered racist vitriol from teammates and the public alike. Joe DiMaggio’s parents were among the thousands of German, Japanese and Italian immigrants classified as “enemy aliens” by the government after Pearl Harbor was bombed by Japan.

Roberto Clemente (Puerto Rico), Fernando Valenzuela (Mexico) and Ichiro Suzuki (Japan) opened the game to talent beyond the frontiers of race and nationality.

The exhibition, organized by the National Museum of American Jewish History in Philadelphia, includes photographs, memorabilia, video clips and even a simulation game in which visitors can “field” balls in the outfield.

The Skirball augments the exhibition by highlighting local heroes, including former L.A. Dodger Sandy Koufax, the first major leaguer to pitch four no-hitters and whose decision not to pitch Game 1 of the 1965 World Series because it fell on Yom Kippur demonstrated the importance of personal beliefs.

“For an American Jew to give his Jewish identity such prominence was a significant moment in the 1960s, when the Jewish community was still not entirely unselfconscious about its place in society,” Kirschner said. “Now we have Jews everywhere, in positions of leadership; it’s no longer unusual. Back then, Sandy Koufax was very conscious of what he represented to so many people.”

The exhibition also explores women in baseball and our notions about what a woman should look like and do. Girls who were selected for the All-American Professional Girls Team, 1943-54, were chosen as much for their looks as for their athletic prowess. They wore shorter uniforms and were given a charm-school guide, which encouraged them to wear red lipstick before they hit the field, curl their hair and refrain from smoking.

The exhibition also explores women in baseball and our notions about what a woman should look like and do. Girls who were selected for the All-American Professional Girls Team, 1943-54, were chosen as much for their looks as for their athletic prowess. They wore shorter uniforms and were given a charm-school guide, which encouraged them to wear red lipstick before they hit the field, curl their hair and refrain from smoking.

“Chasing Dreams” looks at baseball as a reflection of the best and worst in American society: the astonishing number of superb athletes, the magic of the game to build community and loyalty—but it does not ignore the ugliness of racism and hatred.

Ben Sakoguchi takes this dichotomy head on. He is interested in telling a people’s history of baseball beyond the statistically interesting moments. He wants to tell the story behind the story, the people behind the baseball.

Sakoguchi is the son of an immigrant Japanese grocer who along with 100,000 Japanese Americans was incarcerated during World War II. His father believed in the American Dream and loved baseball.

For his canvases, Sakoguchi copies the style of vintage orange crate labels, a format familiar to him from having worked in his father’s store. Each piece displays a brand, an orange and a town. “These are not real orange crates, they’re all imagined, but really embody the orange crate imagination,” says Skirball Curator Clancey. “Some of the towns are long gone, but they were all towns at one point.”

Los Tomboys Brand features women playing baseball, often as co-owners and as players. Los Chorizeros (the sausage makers) was one of Southern California’s best Mexican American baseball teams.

In the section on Segregation-Desegregation, Sakoguchi shows people who represent the push for equality in baseball and people who represent the worst.

Black Bucks Brand features Dock Ellis, an outspoken pitcher who advocated for the rights of players and African Americans, celebrating the moment when the Pittsburgh Pirates fielded an all-African American baseball team.

Gamblin’ Rose Brand depicts Baseball Commissioner Bart Giamatti as an umpire watching Pete Rose sliding around the field in clubs and spades. Giamatti negotiated the agreement terminating the Pete Rose betting scandal by permitting the outfielder/ manager to voluntarily withdraw from the sport to avoid further punishment.

Busted Brand shows rightfielder Sammy Sosa at bat, with a reference to his steroid use in the lower left-hand corner that reads: “Full O Juice.”

Sakoguchi’s body of work and “Chasing Dreams” explore America’s pastime and reflect both the highs and lows of American culture.

The exhibitions continue through September 4. Contact: (310) 440-4500 or skirball.org.

Jackie Robinson signing autographs on the first day of spring training with the Brooklyn Dodgers, March 6, 1948. Photo donated by Corbis

Ticket to opening day at Ebbets Field, April 15, 1947. Loan courtesy of Stephen Wong

Ben Sakoguchi, Debutantes Ball Brand, 2005. Acrylic on canvas.

Ben Sakoguchi, Gamblin’ Rose Brand, 2008. Acrylic on canvas.

Ben Sakoguchi, Hair Ball Brand, 2008. Acrylic on canvas.

Hank Greenberg and Joe DiMaggio. Photo donated by Corbis

By LIBBY MOTIKA, Palisades News Contributor

You must be logged in to post a comment.