By Bob Vickrey

Special to the Palisades News

As I reported for my first day of work in October 1972 and entered the creaky Boston office headquarters of America’s oldest publishing house, I thought perhaps that I had stepped back into the 19th century.

Houghton Mifflin had indeed been linked to that century by publishing authors such as Emerson, Thoreau, Longfellow and Harriet Beecher Stowe.

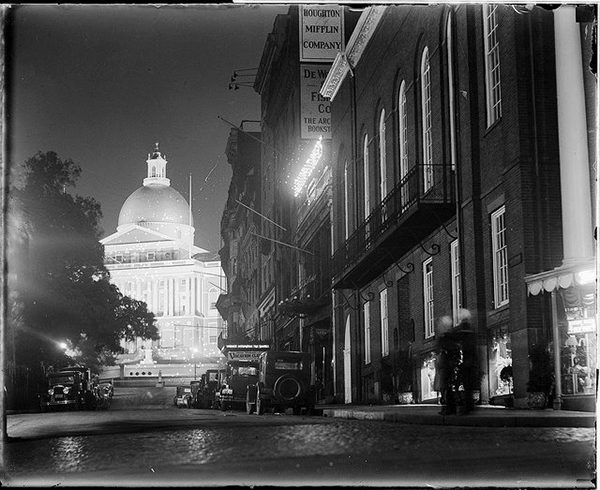

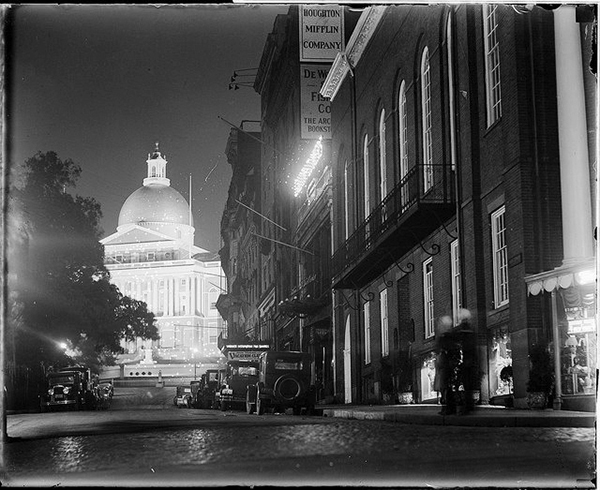

One could witness the history preserved there by simply walking the hallways of this 100-year-old charming, but well-worn brick structure located on Park Street just down the block from the ornate Massachusetts State House. The front side faced Boston Common and the backside office windows looked out on the Boston Granary, which was home to considerable Colonial history, including the gravesites of Paul Revere, Samuel Adams and John Hancock.

I was taken to the third floor by an outdated elevator that was referred to as the “birdcage” by its gracious operator, Mrs. Williams, whose tenure I imagined as dating back long enough to have escorted the distinguished Mr. Emerson to his appointments with his editor.

I had been hired in the sales department as a representative, whose job it would be to present the company’s forthcoming books to independent bookstores throughout Texas and the Southwest. At that moment, it was impossible to envision the enormous changes across the bookselling landscape awaiting in the years ahead that would per- haps eventually steer my career—at least metaphorically speaking—toward my own marble headstone in that backyard Granary.

Houghton Mifflin was no longer a dominant force in publishing as it had been in the first part of the 20th century, but by the time I had arrived it was still actively publishing bestselling authors like John Kenneth Galbraith, Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., and J.R.R. Tolkien. The whole place was alive with its grand history, and for a young buck like me, I thought I’d died and gone to heaven, having been surrounded by the many literary

icons of merging centuries. The president of the company sat at Longfellow’s desk and the editorial director once occupied Nathaniel Hawthorne’s.

It now occurs to me that with all that his- tory at play in this impressive vault called 2 Park Street, there would be little wonder why traditional publishing failed to keep up with modern business trends and models. Among the many categories Houghton published, poetry was always the one genre known for commanding a certain cultural distinction, but often yielding little in consumer sales. Let’s face it, a company’s mission statement that even remotely implies “for the greater good” is not a message that generally en- dears itself to an accounting department.

The editorial leadership there fully understood the nature of its mission, and thus forced the inevitable collision at the inter- section of culture and commerce. The two forces simply never meshed—yet no apology was offered by anyone in the company who had knowingly taken the symbolic “vow of poverty” when we signed up for our jobs.

Publishing was born of a romantic notion, seemingly armed with a noble calling that flew completely in the face of any basic business principles that required yearly growth in sales. Therein lies the rub for that persnickety group called “the Board of Directors.”

Out in the marketplace, there were also major shifts afoot in the way books were being bought and sold. The discount book chains changed the retail landscape forever for the independent owners around the country, and the decline in the number of those family-owned stores was swift and dramatic.

Long before online book buying and downloading to hand-held digital devices from Amazon became the rage among consumers, I was already being greeted in my neighborhood by my friend and veteran writer Josh Greenfeld as “the village blacksmith.” He tried to gently warn me that my obsolescence was just beyond the horizon.

When Houghton’s general book department eventually moved from its venerable headquarters into the upscale glass towers only a few blocks away, the move essentially signaled an end to publishing’s past and introduced the beginning of contemporary corporate life. After Park Street was abandoned, the aging structure housed nothing more than the memories and voices of the company’s distinguished history.

When Houghton Mifflin merged with Harcourt Publishing in 2008, the new firm found itself fighting for survival in a fierce battle being waged in a digital world in which the whole publishing industry was caught virtually unprepared.

Upon reflection, I now realize that my role had become as outdated as that misunderstood poet who had lost his voice long ago within the corporate system. Neither of our missions translated within that culture and we both had unwittingly encountered the same inevitable destiny as that ill-fated village blacksmith.

I worked in an earlier era graced by a certain manner of old-fashioned courtliness that was defined by the closely interconnected relationships between authors, editors and staff members, as we found inspiration in watching talented new writers ascend to literary stardom.

And even in later years, after many of us veterans had become tired and skeptical about whether publishing miracles could still happen, we acknowledged that these splendid moments are what ultimately embolden and sustain publishing dreams for both the writer and publisher.

One of those moments happened recently when I learned that one of my best friends here in town, Alan Eisenstock, the author of 14 previous books, is publishing his latest book with my “alma mater,” Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. His book Hang Time: My Life in Basketball, which he co-authored with Elgin Baylor, is due out April 10. His editor in Boston is my longtime friend, Susan Canavan, who is one of the finest editors in the business.

This has once again reminded me that despite our occasional skeptical protestations, publishing dreams remain very much alive today—even for old cynics like me.

Bob Vickrey is a longtime Palisadian and a regular contributor to the News. He also writes for the Houston Chronicle and theWaco Tribune-Herald.

You must be logged in to post a comment.